100-Year Journey of the Palace Museum

China’s Palace Museum continues to evolve in step with the times with an open and collaborative spirit, telling a compelling story of how an ancient civilization embraces the modern world while taking innovative steps towards the future.

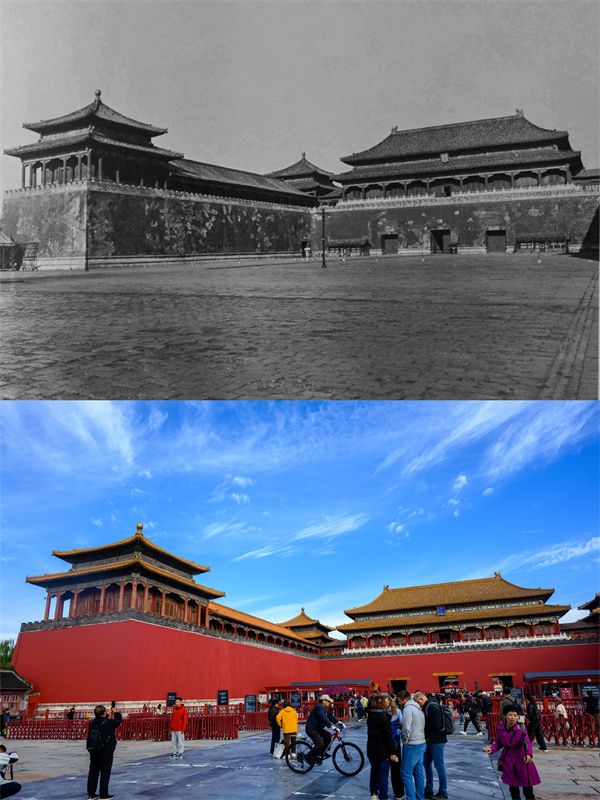

On October 10, 2025, China’s Palace Museum ushered in its 100th anniversary. Being a unique symbol of China’s ancient history and an icon of its civilization, it emerged from the tides of modern social transformation and is progressing in step with the rest of the country in its journey towards rejuvenation.

From Forbidden City to the people’s museum

On the Meridian Gate Tower of the Palace Museum, the exhibition “A Century of Stewardship: From the Forbidden City to the Palace Museum,” held in honor of the museum’s centenary, was opened on September 29, 2025. Through three sections which feature 200 cultural relics (sets), the exhibition traces the museum’s journey from inception and struggle to recent progress and ongoing innovation.

Here, visitors can appreciate various historical treasures like the painting Along the River during the Qingming Festival, admire the 3,000-year-old wine vessel Yachou Square Zun, and ponder the profound symbolic golden Jin Ou Yong Gu Cup. Shoulder to shoulder, guests wander through this cultural paradise that now belongs to the people. As if in a dialogue with history, visitors seem to be transported back in time to the day when this place first opened its doors as the Palace Museum.

The Palace Museum was officially opened on October 10, 1925. When the news came out, a sensation surged through the residents of Beijing, and they began to flock to see inside the once-forbidden imperial palace.

A newspaper report from that time vividly captured the scene, “For millennia the majestic palaces were beyond the reach of ordinary people. People are now allowed to stride proudly through, look around, and talk freely within their walls, for just a small fee … The crowds surged forward so thickly that one could not even turn around. The halls were packed and a sea of visitors were swept along helplessly by the flow.”

However, after the excitement subsided, a formidable challenge emerged: how was the palace to be restored to its former glory, as its buildings had fallen into disrepair and courtyards were overgrown with weeds? The first and most pressing issue was to build a museum collection.

The pioneering guardians of the Palace Museum began by taking stock of the palace’s assets. Working in teams, they used the most basic methods to seal the various halls and conduct a meticulous inventory of the palace’s items. This unprecedented inventory and registration effort continued until March 1930. It not only created archives for millions of cultural objects but, more importantly, established the enduring principle of “state treasures are publicly owned.” This foundational work marked the beginning of a new chapter in the Palace Museum’s history as a public institution.

According to inventories of cultural relics which the Palace Museum conducted since its beginning, one before 1949 and four more between 1949 and 2010, the artifacts in its collection documented down to the last item – 1.95 million objects (sets) in 25 broad classes and over a hundred sub-categories.

However, the Museum’s journey of development has not been all smooth sailing. In February 1933, invading Japanese forces advanced in China. After the Shanhaiguan Pass fell, the Beijing-Tianjin region was in immediate danger. To safeguard its priceless collections, the Museum organized the monumental evacuation of its artifacts, shipping them in batches to southern China. This effort became one of the most epic treks in the history of global cultural heritage preservation. Nearly 20,000 crates of artifacts embarked on a journey that lasted over two decades and spanned tens of thousands of miles. Thanks to the dedication of countless guardians who vowed to protect the artifacts with their lives, these treasures were eventually returned to the Palace Museum after the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, ensuring the continuity of this invaluable cultural legacy.

Today, some artifacts that endured this southward evacuation journey, such as the 10 stone drums from the Tang Dynasty (618-907) – hailed as a “premier ancient artifact of China” – are displayed in the eastern part of the Museum. Standing before these drums, one can still discern the ancient seal scripts inscribed upon them – a testament to the enduring continuity of Chinese civilization.

From 1949 to 2019, the Palace Museum received a cumulative total of 456 million visits. In 2009, annual visits surpassed 10 million for the first time, and by 2024, the number exceeded 17.6 million. Today, the Palace Museum stands as a cultural landmark of China that is capturing the attention of people from around the world.

As Shan Jixiang, former director of the Palace Museum, stated, the establishment of the Palace Museum transformed the once-forbidden imperial palace, previously accessible only to royal members, into a space accessible to all visitors, and turned treasures once enjoyed exclusively by a few into the shared wealth of the entire nation. This transformative shift pioneered the modern Chinese museum movement and marked a groundbreaking milestone of historic significance.

A beacon of cultural inheritance

Beginning on September 30 of this year, the first two courtyards of the Garden of the Palace of Tranquil Longevity were opened to the public. Known as the Qianlong Garden, this luxurious garden was not only the residence for Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799) in his later years but also a reflection of the exquisite design of ancient Chinese landscaping.

Though compact in size, it showcases the meticulous craftsmanship of ancient Chinese royal gardens in each detail. Strolling through it, you can feel as though you were walking across a 3D scroll of a classical Chinese painting. People who come here will also enjoy looking at remarkable 18th-century Chinese architecture, landscaping, and decorative arts.

The rebirth of the Qianlong Garden was the result of a 25-year-long cultural relic restoration. Starting in 2000, the Palace Museum joined hands with the World Monuments Fund (WMF) for the protection and restoration of the garden. Li Yue, a senior engineer at the Palace Museum, joined the Qianlong Garden project team in the museum’s ancient architecture department in 2008. According to her, the work of restoring the garden involved a vast amount of intricate craftsmanship: the embroidery took over 30 artisans more than a year to complete; the scaled sample took 40 staff members over two years to finish; and the process of restoring the panoramic paintings in the Juanqin Studio lasted for more than three years. Every detail embodies utmost respect for the original historical appearance.

As a hub of outstanding traditional Chinese culture, every artifact in the Palace Museum embodies the wisdom of ancient artisans. The vast majority of these treasures are former imperial collections from the Ming and Qing dynasties, including 180 rare and precious books included in the National Catalogue of Precious Ancient Books.

Protecting these national treasures requires immense patience and superb skills. On the western side of the Palace Museum stands a row of modest single-story buildings, home to what is often described as the world’s largest conservation center for cultural relics. There, over a hundred experts utilize modern scientific technologies to “diagnose” and systematically “treat” artifacts. The facility is fully equipped with specialized spaces such as laboratories for conservation of organic artifacts, ancient paintings and calligraphy, as well as textiles. It is here that traditional craftsmanship and cutting-edge technology are deeply integrated.

The Palace Museum’s tradition of restoring ancient books dates back to the late 1920s, when its library began employing full-time binders and conservators. In 1947, Xiao Fu’an, a master in the field of restoring ancient books, joined the Palace Museum and helped created a dedicated team that has been maintained for four generations. For decades, conservators have adhered to principles such as repairing old things to look old, prioritizing restoration, minimal intervention, and reversible processes. They have restored approximately 900 volumes (pieces) of important ancient books since the year 2000. Recognized for its robust professional expertise, the Palace Museum was recently designated as one of the “second batch of National-Level Ancient Book Conservation Centers” by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, solidifying its authoritative status in the field of cultural heritage preservation.

In the woodcraft restoration workshop, conservator Huang Qicheng utilizes 3D printing technology to create simulated models for replacing missing carved components. A piece barely the size of the palm of a person’s hand took the team six months of trial and error to restore it to its former state. In his view, regardless of whether the object is an imperial throne or everyday object, every artifact is an indispensable link in the cultural heritage chain, and his responsibility lies in maximizing its life span while preserving its value.

Five Oxen, a Tang-Dynasty painting by Han Huang, was riddled with holes and mold stains after it was returned to the museum. In 1977, restoration expert Sun Chengzhi, then approaching 70, took on the arduous task of restoring it. Carefully studying each damaged area repeatedly with a magnifying glass, he spent eight months of performing complex procedures, such as washing, decontamination, paper patching, and recoloring, before finally restoring the oldest preserved Chinese painting on paper to its original brilliance. In the early years of the People’s Republic of China, a group of master artisans from across the country came together at the Palace Museum, cultivating new talent through hands-on practice and gradually building a structured, skilled artisan team.

Meanwhile, technological innovation is also making a profound impact on conservation approaches. The Palace Museum has established long-term systematic collection mechanisms: by the end of 2025, over 1 million artifacts – more than half of the total – will have been digitized. The Digital Collection Archive, has released high-resolution images of more than 100,000 items since it was launched in 2019, allowing the public to engage with national treasures from the comfortableness of their homes. According to Zhu Hongwen, deputy director of the Palace Museum, the institution continuously explores new paths for integrating culture and technology. By applying digital twin technology, an intelligent management platform is being built that covers architectural conservation, artifact management, and visitor services, ultimately enabling personalized virtual exhibitions, cross-temporal multi-user tours, smart public service management and much more.

Having weathered a century of change, the Palace Museum has built a comprehensive conservation system that integrates research, restoration, and setting international standards, and is supported by both technology and craftsmanship. With six national-level intangible cultural heritage projects, it restores over 300 artifacts annually. In 2024, the Palace Museum established a research institute to further systematize academic studies.

Cultural exchanges

On June 10, 2025, the inaugural International Day of Dialogue among Civilizations, the Palace Museum hosted a cross-civilization gathering – the “Diplomats at the Palace Museum” event. Over 40 ambassadors and diplomats from nearly 30 countries visited the exhibition “A Dialogue between Chinese and Foreign Garden Cultures.” In the exhibition, Claude Monet’s Water Lilies was displayed alongside the Lotus by Shi Tao from the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911). This curatorial approach stemmed from an in-depth collaboration between the Palace Museum and the Art Institute of Chicago, in which they used gardens as a universal language to showcase different civilizations’ interpretations of nature, aesthetics, and philosophies of life.

As noted by Georgian Ambassador to China, Paata Kalandadze, “Regardless of how many times you visit the Palace Museum, it always reveals new beautiful facets.”

Since 2012, the Palace Museum has introduced nearly 30 cultural exhibitions from Asia, Europe, and the Americas, organized 79 exhibitions in foreign countries and in China’s Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan, and participated in 29 collaborative exhibitions overseas. From “The Forbidden City and the Palace of Versailles” to “Historic Encounters: Interaction between China and West Asia in History,” these exhibitions highlight the ongoing material and intellectual dialogue between China and the world. Behind these efforts lies a deep collaboration between the Palace Museum and global cultural institutions in academic research, heritage conservation, and digital innovation.

These in-depth exchanges are facilitated by international platforms. In August 2022, the Palace Museum launched the “Taihe Scholars” program, inviting global museum experts to conduct research within the palace walls for several months. Foreign scholars participated in the daily academic activities alongside their Chinese counterparts, fostering mutual learning through teaching and research. By the end of 2024, the program had supported 27 scholars from 14 countries and regions, building academic bridges across the world.

Meanwhile, the Taihe Forum, established in 2016, has become a key dialogue mechanism in the global cultural heritage sector. On October 11, 2025, the seventh Taihe Forum was held in Beijing, bringing together over 300 representatives from 26 countries across five continents to discuss museum operations, sustainable development of world heritage, and the integration of culture and technology. At the forum, participants not only shared experiences but also took on the responsibility of setting industry standards. The Palace Museum also serves as the secretariat of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) Technical Committee for the Protection of Cultural Heritage Conservation (ISO/TC 349), integrating Chinese expertise into international norms.

From 1925 to 2025, the Palace Museum has been transformed from an imperial palace into a globally renowned cultural landmark. Today, it has become both a vital bearer of 5,000 years of Chinese civilization and a living showcase of Chinese culture for cross-cultural dialogue.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +