China’s Evolving Role in Global Climate Diplomacy

The success of China’s approach, both domestically and overseas, will influence not only its own development but also the global pathway toward a more sustainable future.

As the world gathers in Belém, Brazil, for the 30th UN Climate Change Conference, COP30, global attention is once again turning to China. For years, China was primarily discussed as the world’s largest carbon emitter. Today, that picture is more complex. China is also the largest builder of renewable energy infrastructure, a key driver in lowering global clean-tech costs, and a major contributor to international climate cooperation.

With this year’s summit focused on moving from pledges to implementation, China has the opportunity to demonstrate how its domestic transition and overseas partnerships are shaping global climate action.

China’s “dual carbon” vision and domestic progress

China’s current climate strategy is focused on its “dual carbon” goals: peaking carbon emissions before 2030 and achieving carbon neutrality before 2060. These goals are serious commitment that influence national planning, industry development, and investment priorities. In recent years, China has directed significant resources toward expanding renewable energy capacity and application in national economy, advancing electric vehicles, upgrading its power grid, and improving energy storage.

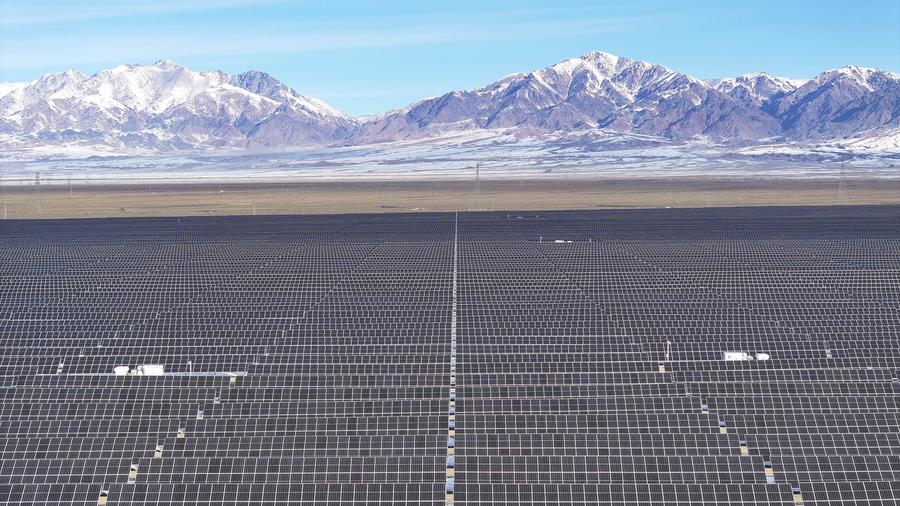

According to the World Economic Forum, China invested around $818 billion in its energy transition in 2024, more than any other country, and about one-third of all global clean energy investment that year. Much of this investment has translated into visible progress. China’s solar power capacity has now surpassed 700 gigawatts, more than the rest of the world combined. Large-scale wind power bases in provinces such as Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang, as well as offshore coastal zones, continue to expand. Meanwhile, the rapid adoption of electric vehicles has reshaped China’s transportation sector, with more than one in three new cars sold domestically now running on electricity.

Another important factor in China’s progress is infrastructure. The country’s high-speed rail network, now the largest in the world, provides millions of daily passengers with a lower-emission alternative to air and road travel. At the same time, grid modernization efforts are helping the system absorb fluctuating renewable supply. However, coal still serves as a stabilizing backup. The approach China has taken is to build renewable capacity first and phase down fossil fuels gradually, rather than abruptly. This strategy remains debated, but it reflects China’s priority on energy security as it transitions at scale.

Turning domestic experience into global partnerships

At COP30, China is emphasizing cooperation, particularly with developing countries that are still expanding basic energy services and infrastructure. Rather than limiting its engagement to diplomatic statements, China has increasingly linked climate cooperation to real financing and construction. This approach has positioned China as a partner in sustainable development for many countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East.

In the first half of 2025, Chinese entities supported about $9.7 billion worth of overseas renewable energy projects, adding 11.9 gigawatts of clean power generation capacity, according to the Green Finance & Development Center. That amount of power, depending on demand patterns, could cover the typical electricity needs of a major global city. These projects range from solar parks and onshore wind farms to hydropower stations and localized mini-grid systems.

In Brazil, the Chinese state-owned SPIC has invested in expanding wind and solar energy installations, a particularly relevant development given that COP30 is being hosted in Brazil this year. In Pakistan, the Karot Hydropower Plant, financed and engineered by China, now supplies clean electricity to millions of residents. Across parts of East Africa, Chinese-supported micro-grid solar systems are helping rural communities access power without waiting for large transmission lines to be built.

These partnerships reflect a core feature of China’s climate role: applying domestic experience to the needs and constraints of other nations. Rather than exporting a single model, China tends to provide technology, financing, and industrial capacity. At the same time, partner governments determine how those resources fit their own local needs and development plans. This allows renewable expansion to progress in places that otherwise struggle to secure funding or technical expertise.

Challenges, expectations, and the road ahead

China’s climate transition is still unfolding, and tensions accompany it. Coal remains a substantial part of the energy mix, and Chinese companies are still involved in some coal-related developments. However, these have decreased since China pledged in 2021 to stop building new coal power projects abroad. At home, coal accounted for 53.2 percent in total energy consumption of the country in 2024, 14.2 percentage points down over the past 11 years. Chinese officials argue that maintaining energy security is essential. At the same time, renewable infrastructure continues to scale, and reductions in fossil fuel dependence will come more rapidly once grid and storage systems mature further.

Diplomatically, China positions itself as a bridge between developed and developing countries. It emphasizes that climate action must accommodate economic development and poverty reduction, particularly in the Global South. Many emerging economies agree with this stance, even as some developed countries call for faster emissions reductions.

What happens after COP30 will be important. China’s next round of climate commitments, expected in the years following the summit, will show whether the country plans to accelerate its phase-out of fossil fuels and align more closely with the 1.5°C global warming limit. Its role in international climate diplomacy will increasingly depend on how its policies evolve at home and how consistently its overseas investments support low-carbon pathways.

Looking towards the future

China’s role in global climate diplomacy is no longer defined solely by emissions. It is shaped by the extent of its renewable energy expansion, the affordability of the clean technology it produces, and the partnerships it forms abroad. As COP30 unfolds in Belém, the central question is not whether China supports climate action, but how effectively it can continue to translate goals into action. The success of China’s approach, both domestically and overseas, will influence not only its own development but also the global pathway toward a more sustainable future.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +