China Is Not Our Enemy

China is not the U.S.’ enemy. It is a rising nation pursuing its own development, security and prosperity—just as any country would.

In recent years, a troubling narrative has gained momentum in the U.S.: China is America’s foremost adversary, a threat to our way of life and a rival to be contained. This view—once a fringe perspective—has now become a bipartisan rallying cry. Tariffs, sanctions, technological restrictions and political hostility are increasingly justified not on strategic grounds, but on the assumption that confrontation with China is inevitable.

But is it? Does China truly seek to undermine the U.S., dominate the world or overturn the global order? The facts suggest otherwise. China is not the U.S.’ enemy. It is a rising nation pursuing its own development, security and prosperity—just as any country would. The choice to turn this into a zero-sum contest lies not in Beijing, but in Washington.

Not seeking domination

At the heart of China’s national trajectory is the goal of national rejuvenation—a long-standing aspiration to restore dignity, prosperity, and global respect after a century of foreign humiliation, civil war and poverty. This goal is not built on ideology or expansionism, but on a desire to provide a better life for the Chinese people.

Over the past four decades, China has lifted hundreds of millions of its citizens out of absolute poverty, modernized its infrastructure and emerged as a global center of manufacturing, innovation and trade. Its achievements are not about challenging the U.S.—they are about ensuring national stability and fulfilling the basic aspirations of its population.

China’s development model is not perfect, nor is it universally applicable. But it is not being exported or imposed on others. Beijing does not seek to remake the world in its image; it seeks recognition as a legitimate and respected voice in global affairs.

China does not seek to replace the U.S. as a global hegemon. Instead, it advocates for a multipolar world, a more balanced international order where power and responsibility are shared, and where countries, large and small, have a voice.

This includes strengthening institutions like the United Nations, the Group of 20, the BRICS group and the Belt and Road Initiative (proposed by China to boost connectivity along and beyond the ancient Silk Road routes—Ed.) It also means reforming outdated systems to better reflect today’s global realities, especially the aspirations of the Global South.

China’s emphasis on sovereignty, mutual respect and non-interference is not a rejection of global cooperation. It is a call for partnership based on equality, not hierarchy.

Much of the current U.S. anxiety about China centers on the question of Taiwan and the South China Sea. But these are either China’s internal issues or regional matters, best addressed by the parties directly involved.

The Taiwan question is a Chinese internal affair—a complex, historic issue rooted in the legacy of civil war. It is up to people on both sides of the Taiwan Straits to find a peaceful resolution and pursue their own path toward eventual reunification. Outside interference only complicates this delicate process and raises the risk of misunderstanding.

Similarly, disputes in the South China Sea should not be viewed through the lens of great power competition. China has already successfully resolved land border disputes with 12 of its 14 neighbors. It is fully capable of working out maritime differences with ASEAN countries through dialogue, negotiation and regional diplomacy. These are not global flashpoints, but regional challenges that require patience—not provocation.

Friend or foe?

A growing obstacle to U.S.-China relations is not ideological difference or economic friction—but rhetoric. When the U.S. labels China as an adversary, competitor or threat, it closes the door to genuine engagement. China has made clear—repeatedly and consistently—that it cannot engage in meaningful strategic dialogue or deep cooperation with a country that fundamentally questions its legitimacy or seeks to contain its rise.

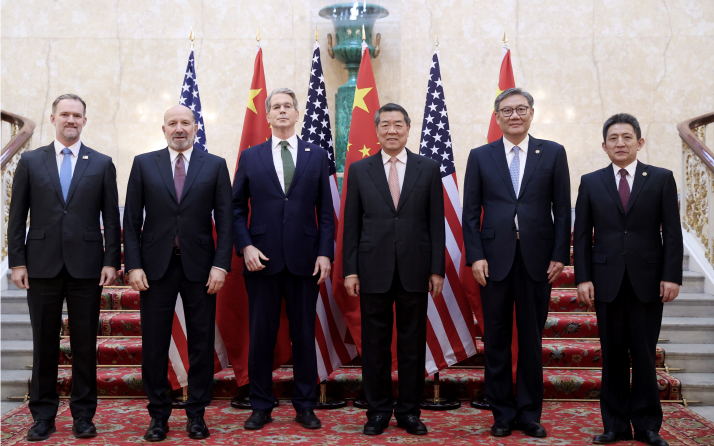

Diplomacy cannot function in an atmosphere of hostility. The principle of mutual respect is not a diplomatic formality —it is the foundation for any productive relationship. No country, including China, will cooperate with a partner that speaks of containment while asking for collaboration.

If the U.S. truly wants dialogue, it must first change the tone—recognizing China as a sovereign nation with its own path and interests, not an adversary to be managed or a rival to be defeated.

Framing China as America’s enemy may serve short-term political agendas, but it is generating long-term harm. It distorts policy, erodes trust and fuels hostility across society. The rise in anti-Asian hate is, in reality, anti-China and anti-Chinese hate. U.S. politicians—who fan the flames of anti-China sentiment—often hide behind the vague term “Asian” to avoid accountability for the discrimination they enable.

This isn’t just political rhetoric—it has real and devastating consequences: assaults on Chinese Americans, suspicion toward students and scholars and targeted scrutiny of Chinese businesses. Careers have been destroyed, communities have been shaken and a chilling climate of fear has taken root.

This fear damages the U.S. itself, undercutting the nation’s claim to fairness, pluralism, and openness—the very ideals it says it defends.

Meanwhile, academic exchange programs are being dismantled, visas are being denied and scientific partnerships are being broken—all in the name of national security. China and the U.S. are drifting toward confrontation not by necessity, but by political design.

More importantly, this artificial rivalry blinds us to shared global challenges. Climate change, public health, food security and responsible technological governance require cooperation—not confrontation. If the U.S. and China cannot work together on these existential issues, the world will be the one that suffers.

The U.S. faces a choice: to continue down the path of rivalry, distrust and escalation—or to step back and reimagine its relationship with China based on realism, mutual respect and shared responsibility.

The U.S. doesn’t need to agree with China on everything. But it does need to understand China as it is. China is not a threat just because it is different. It is a sovereign nation with its own history, priorities and global role to play.

The author is president of the America China Public Affairs Institute, and chairman of the Partnership for Peace and Prosperity.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +