Common Prosperity: a Goal for All Governments?

China’s ‘common prosperity’ policy is a multidimensional pursuit of social and economic progress aimed at full realization by 2050.

Achieving common prosperity – prosperity that is universally shared – has been a longstanding aspiration of the Chinese government. It should be the ambition of any government committed to the wellbeing of its people.

Now, in China, common prosperity is not just an aspiration but a policy objective to be fully achieved by a given date.

Scholars track the origins of common prosperity to China’s Warring States period some 2,000 years ago. However, in the modern era, the concept flowed from the pen of Mao Zedong who is credited with personally masterminding the Resolution on the Development of Agricultural Production Cooperatives dating from December 1953. This envisaged that rural cooperatives would enable farmers to gradually and completely get rid of poverty and achieve a life of common prosperity.

In 2015, when making the recommendations for formulating the 13th Five-Year Plan for Economic and Social Development (2016–20), the 18th Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee sought to ensure that all people have a greater sense of gain in the process of jointly building and sharing development – steadily moving towards common prosperity.

With extreme poverty successfully eradicated in 2021, common prosperity was incorporated into the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) as one of the key objectives in achieving basic socialist modernization by 2035. Moreover, the fourth plenary session of the 20th CPC Central Committee in 2025 made it a foundational justification for the 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-30), namely: the all-round development of people and common prosperity for all people.

There is, then, remarkable continuity from the path delineated by Mao’s aspiration to get rid of poverty, its fulfilment under the leadership of President Xi Jinping, and to now the path of realizing “solid progress” towards common prosperity by 2035 before its full achievement in 2050.

Interestingly, though, common prosperity has never been precisely defined.

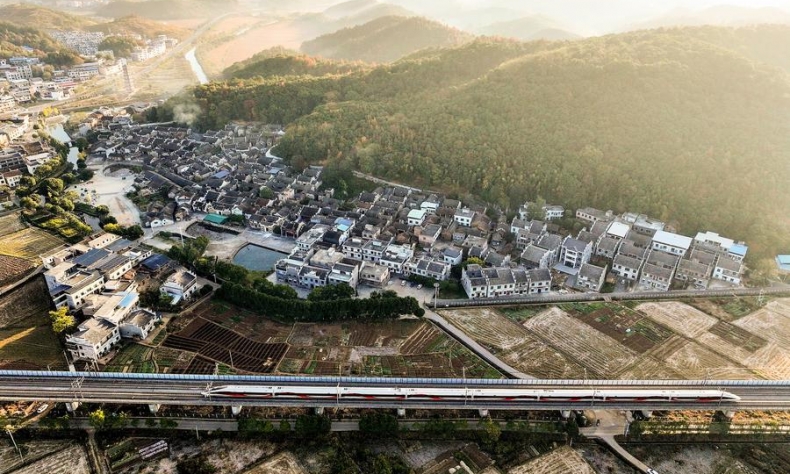

However, the Chinese language can cope with greater ambiguity than English which drives other legislatures towards detailed regulations. Chinese law, too, tends not to be prescriptive but restorative; not solely looking backwards to determine guilt but also forwards towards reconciliation. Moreover, Beijing’s legislation needs to be sufficiently flexible to cope with its enormous geographic, economic and cultural diversity that characterizes China.

President Xi Jinping has on many occasions referred to common prosperity as a process. It is the process of transforming China’s current income distribution, which he likens to a pyramid with many individuals located towards the base, into the shape of an olive with very few people at the top and bottom.

It is also clear that common prosperity is not solely concerned with economics but is about social progress too.

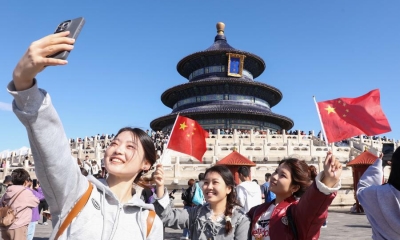

It responds to the people’s yearning for a good life, bringing spiritual fulfilment as well as material possessions.

There are, though, advantages stemming from a shared understanding of the meaning of common prosperity. It facilitates goal setting, monitoring of progress and policy learning, preventing mistakes, and optimizing outcomes. In this regard, Zhejiang, being designated as a pilot province in 2021, is leading the way.

There has been a noticeable refinement in the objectives. Publicly available government documents in 2021 envisaged common prosperity as encompassing six policy dimensions spanning seven broad areas: economic development, income distribution, public services, regional equity, environmental preservation, cultural development, and social governance.

By 2023, there was a reduction to four modules: high-quality economic development; improving public services; modernizing social governance; and narrowing the three major disparities – regional, urban-rural, and income. A year later only the narrowing of disparities was emphasized alongside high-quality development as the foremost priority for the Zhejiang demonstration zone.

The same emphases were evident in discussions on China’s 15th Five-Year Plan (2026-30) at the fourth plenary session of the 20th CPC Central Committee in October 2025.

The meaning of “high-quality development” needs to be inferred from words and practice. The shift from growth based on excessive resource consumption and low-value manufacturing to intelligent, green, and high-value-added production is evidenced, for example, by programmes of tax incentives and skill development.

The academic community has been investing its energy in better understanding the meaning of common prosperity, trying to best guess the intentions of policymakers. The initial result was a multitude of different definitions that were operationalized in disparate ways that limited the potential for replication, testing and cumulative learning.

However, there is increasingly a coalescence of views as to the meaning of common prosperity and some coherence in the way that it can be best measured to determine China’s direction of progress.

There is perhaps universal agreement on the importance of distinguishing between the level of income and other resources and their distribution. This means that the shape of the metaphorical olive needs to be considered as well as its size.

In policy terms, it implies that, while the rate of economic growth is significant, the nature of the growth is equally important, especially who benefits from the process of development and how the benefits of growth are shared. These considerations give further meaning to the concept of high-quality development.

Earlier this year, a Sino-German research team published a study, led by Dr Zhang Junlai, showing that the lifetime income of the average Chinese citizen increased almost 12-fold between 1990 and 2019. This translates into an average annual growth rate of 9.21 percent. However, adjusting the indicator to account for income distribution pointed to an annual improvement of just 8.63 percent due to a marked increase in income inequality.

When changes in life expectancy and variations in health status were factored into the index, annual improvement over a slightly shorter period (1990-2015) was 8.56 percent. Although noticeably lower than the rate of economic growth, China’s policies delivered a much greater increase in this index of individual wellbeing than many comparable countries. Using the same index, wellbeing in India improved at an annual rate of 2.94 percent over the same period.

There is increasing agreement among academics that common prosperity is inherently multidimensional. There are parallels here with China’s approach to poverty alleviation. Whereas poverty is typically measured as a lack of income, China’s poverty alleviation program focussed on “two no-worries, three guarantees,” namely: food and clothing; and education, healthcare, and housing.

There is still debate about the appropriate number of dimensions.

A team led by Professor Wei Rongrong of Wuxi University advocates three dimensions – affluence; shareability and sustainability. The first merges measures of the level of prosperity and variation between individuals and urban and rural areas. Shareability seeks to capture “whether the benefits of reform and development are fairly shared,” ostensibly measuring “the gap between people’s aspirations for a better life and their actual living conditions.” Sustainability is defined as “the long-term capacity for common prosperity” and as “the degree to which economic and social development matches population, resources, and environmental carrying capacity.”

Professor Wang Yuhan (China Jiliang University, Hangzhou) and his team insist on four dimensions of common prosperity: material wealth; harmonious social life; a rich cultural life; and a livable ecological environment. Their indicators of harmonious social life relate to the coverage of health services and pensions, to home size, car ownership and to the unemployment rate. A rich cultural life is indexed by public spending on education and residents’ spending on “education, culture and entertainment,” while a “livable ecological environment” includes measures of green space, forest cover, and sewage and waste treatment.

Professor Wang’s team created a single measure of common prosperity from their four dimensions and were able to demonstrate that regions and cities along the Yangtze River Economic Belt had all enjoyed measurable improvements even over the short period from 2010 to 2019. Progress towards higher common prosperity stalled in the leading areas but continued in Yunnan, Jiangxi, and Guizhou, the lowest ranked provinces; they were able to report reducing interregional inequality.

According to Wang’s analysis, Shanghai, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang score top in terms of material affluence. However, with respect to harmonious social life, Shanghai is replaced in third place by Sichuan, which also scores highly on cultural life, joined as the top three provinces by Jiangsu and Hunan.

The challenge for scholars contributing to China’s goal of common prosperity is to determine the policy trade-offs between its different dimensions. The necessary techniques to achieve this exist, for example, structural equation modelling, but have yet been widely used by Chinese scholars studying common prosperity.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +