Fueling a Nation

Tempered by time, the West-East Gas Pipeline Project has become an energy lifeline stretching across China’s vast landscape, embodying the enduring synergy between the country’s western and eastern regions, a living testament to unity, innovation and perseverance.

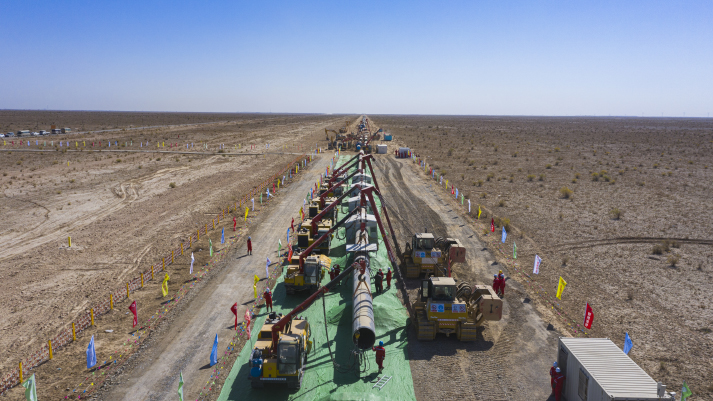

The wind and sand of the Tarim Basin whisper through the Kela-2 gas field, nestled in the southern foothills of the Tianshan Mountain Range in Baicheng County, Xinjiang, carrying echoes of a pivotal moment etched into the annals of China’s development. It was July 4, 2002, when the roar of machinery broke the silence of the desert, signaling the birth of an epic undertaking, the West-East Gas Pipeline Project. Approved by a directive from the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, construction began on what would become a cornerstone of the nation’s energy infrastructure.

This colossal artery of natural gas stretches across thousands of kilometers—bridging vast western resources with its bustling eastern cities, linking north to south and even reaching across borders. It has bolstered China’s energy security and propelled the country toward a low-carbon future.

From scarcity to synergy

As the 20th century drew to a close, China’s economic engine was roaring to life, but its energy framework struggled to keep up with soaring demand. A stark mismatch loomed between the locations of abundant energy resources and the consumption-heavy eastern markets. At that time, coal dominated the energy mix, accounting for over 70 percent of primary energy consumption, while cleaner natural gas made up a mere 3 percent. It was clear: A transformation was urgently needed.

The breakthrough came in September 1998, deep in the sands of Xinjiang, with the discovery of the Kela-2, then the largest integrated natural gas field in China. This seismic find ignited discussion of building a pipeline that could bridge the resource-rich west with the energy-hungry east. In February 2000, the State Council, China’s highest state administrative body, convened a meeting to hear the results of feasibility studies conducted by the State Planning Commission and China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), China’s leading oil and gas producer. The data were compelling: ample reserves, strong market demand and promising economic returns. By August that same year, the project was approved as a flagship initiative under the western development strategy, which was initiated in 2000 to bridge the development gap between China’s prosperous coastal provinces and municipalities and its less developed western regions.

On July 4, 2002, work began in earnest. Just over two years later, on December 30, 2004, the West-East Gas Pipeline entered full commercial operation. Anchored in the Tarim Basin, it delivers natural gas from Xinjiang to other parts of the country, particularly the industrial hubs in the Yangtze River Delta. More than a technical feat, this project signaled China’s decisive shift from a coal-dependent past to a cleaner, gas-driven future and opened a new chapter of coordinated development of the country’s western and eastern regions.

Engineering against the elements

Constructing the West-East Gas Pipeline was nothing short of an odyssey through some of China’s most formidable landscapes. The route cuts across the Gobi Desert, the Loess Plateau and the intricate waterways in regions south of the Yangtze River, while surmounting natural obstacles like the Yangtze and Yellow rivers, terrains long deemed off-limits to major engineering endeavors. Line One of the project alone crosses both rivers, including two daring passes 30 meters beneath the Yellow River’s bed.

In the early stages, foreign experts doubted the project’s feasibility. But Chinese engineers responded with resolve, pioneering pipe-jacking technology. By sinking caissons into the riverbeds and using hydraulic jacks to push concrete pipes through, they created underground corridors for the steel pipelines—a feat akin to threading a needle underwater. This was China’s first successful execution of long-distance, high-difficulty crossings using large-diameter shield tunneling, pipe-jacking and directional drilling.

Yet, it wasn’t just the terrain that tested limits—the climate, too, proved troublesome. The pipeline snakes through the scorching land of Turpan’s Gaochang District and Shanshan County in Xinjiang, where summer surface temperatures can soar to 47.8 degrees Celsius, causing steel pipeline surface temperatures to exceed 70 degrees Celsius. Welders labored in specially designed heat-resistant suits, often in the midst of sandstorms. In the Hundred-Mile Wind Zone, stretching from Xiaocaohu in Shanshan County to Hami City along the southern edge of the Tianshan Mountain Range, where winds above Beaufort 8 blow for nearly 140 days a year and gusts can exceed Beaufort 12, engineers were compelled to innovate. In seismic-prone sections, such as Line Four’s stretch through Xinjiang’s seven fault zones, the builders deployed strain-resistant X80-grade steel pipes—1,219 mm in diameter with walls up to 33 mm thick. These enhancements dramatically increased the pipeline’s earthquake resilience and operational reliability, reducing the number of weld seams by a third and reinforcing structural integrity.

Technological self-reliance was another uphill climb. Initially dependent on imported materials, compressors and welding technologies, China steadily moved toward homegrown alternatives. When constructing Line Two of the project, which mainly supplied by gas from Central Asia and completed in December 2012, domestic breakthroughs included the production of X80-grade steel pipes and the establishment of local compressor maintenance expertise at the Huoerguosi initial compressor station, the first station of the China-Central Asia Natural Gas Pipeline in China. There, engineering teams mastered the dry gas seal technology and completed the country’s first independent maintenance of pipeline transmission compressors—key steps in building a homegrown knowledge base.

As of 2024, the West-East Gas Pipeline Project had evolved into a fully digitized twin-pipeline system, with four main lines stretching over 20,000 km in combined length. Connecting with the pipelines transporting natural gas from Central Asia to China, it has become the longest energy artery of its kind in the world.

Resource-driven transformation

Since Line One of the West-East Gas Pipeline Project began commercial operation in 2004, China’s economic development and urbanization have surged to unprecedented levels. This rapid growth spurred a parallel boom in natural gas demand, leading to the emergence of seven major regional gas markets centered around the Bohai Sea Rim, Yangtze River Delta, southeastern coast, southwest, northwest, central-south and northeast regions. To meet the nation’s escalating energy needs, subsequent lines of the project were launched in quick succession.

Line Two broke ground in 2008 and was completed by 2012. Stretching from Huoerguosi in Xinjiang to Shenzhen in Guangdong Province, and ultimately extending to Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, it traverses 15 provincial-level regions. Line Three followed in 2012, with its western and eastern segments operational by 2014 and 2016, respectively. Construction on the middle section of the line began in 2021 and is progressing rapidly. Line Four, launched in September 2022, brought its Xinjiang section online by September 29, 2024.

Xinjiang remains the engine room of this energy network. The region has leveraged massive pipeline investments to spur infrastructure growth and fuel the chemical industry. The Karamay Petrochemical Industrial Park, once barren desert, has transformed into a nationally recognized petrochemical hub. In 2009, Urumqi became one of the first cities to benefit from Turkmenistan’s natural gas via an extended section of Line Two, which connects China and Central Asian nations, launching its Blue Sky Project and becoming China’s first fully gasified regional capital.

In south Xinjiang, the project also supports public wellbeing by distributing Central Asian natural gas to households and industries alike. At CNPC’s Urumqi Refinery, up to 650,000 tons of synthetic ammonia and 1.2 million tons of urea are produced annually, ranking it among the country’s leading nitrogen fertilizer bases. Meanwhile, Zhongkun New Materials Co. Ltd., located in Bayingolin Mongolian Autonomous Prefecture, processes this gas into textile-grade fibers, forging a vertically integrated chain that links chemical production to textiles and apparel, revitalizing local industry ecosystems.

The pipeline network has also become a flagship energy cooperation project under the Belt and Road Initiative, a China-proposed initiative to boost connectivity along and beyond the ancient Silk Road routes, enabling transnational cooperation as Turkmen and Kazakh hydrocarbons are exported eastward to fuel Chinese megacities. Beyond cross-border energy flows, Xinjiang-based operators are tapping coal-derived methane from the Ili Valley, channeling surplus gas to eastern provinces like Zhejiang, Shandong and Henan—unlocking comparative advantages and broader socioeconomic dividends.

East China, in turn, has embraced a cleaner energy future. After Shanghai was connected to natural gas in 2004, coal gas was phased out within a decade. Sinopec Yangzi Petrochemical Co. Ltd. in Jiangsu Province now uses natural gas to generate an annual output of 20 billion yuan ($2.78 billion). In Shenzhen, the Yuhu Power Plant has eliminated “black rain” emissions, achieving near-zero pollution. Black rain is liquid precipitation polluted with dark particulates, especially soot and ashes (including coal ash) resulting from wildfires, coal combustion or nuclear explosions (a liquid type of nuclear fallout).

As of September 2024, the West-East Gas Pipeline Project had cumulatively transported 980 billion cubic meters of natural gas, replacing 1.3 billion tons of standard coal equivalent and cutting carbon dioxide emissions by 1.43 billion tons.

Tempered by time, the West-East Gas Pipeline Project has become an energy lifeline stretching across China’s vast landscape. Behind its success are the tireless efforts of countless builders who carry forward the spirit of Daqing, the first major oilfield opened up in China in the 1960s: “In front of difficulties, there is us; in front of us, there are no difficulties.” This grand project continues to embody the enduring synergy between the country’s western and eastern regions, a living testament to unity, innovation and perseverance.

The author is a researcher with the Institute of Party History and Literature, Communist Party of China Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Regional Committee.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +