By Marxist Contrast

Capitalists are concerned, particularly those in the West, who equate any type of government regulation or social welfare with a ‘red revolution’ despite their own mantras that Marxism and socialism are themselves dead ends.

No Marxist has ever lived during a period when capitalism didn’t exist, when it wasn’t already globally hegemonic. The argument that some places came to capitalism later, or that they arrived via state capitalism and emphasized social welfare or even socialist values, does hold up. Humanity is now, and has long been, at a time when the capitalist mode of production dominates the world. This is not entirely a bad thing. While Marxists generally point to the many contradictions and injustices associated with capitalism, even Karl Marx himself asserted capitalism could help transform society’s social and material foundations, better preparing people to take new steps toward a new era.

But let us be clear. We are well past the point of debating whether capitalism is, or was, a necessary evil, and, likewise, what it precisely is. Whatever benefits capitalism gave humanity over feudalism, and whoever benefited most, must never obscure the basic facts: As a political economy, capitalism systematically privileges the wealthy—be they wealthy individuals, companies or countries—and normalizes the exploitation of the masses, including their labor, land, air and water.

Historically, this included the enslaving of less developed and more vulnerable populations overseas, including those in Africa, Latin America and Asia, by early capitalist nations. Today, some would argue a more humane capitalism has replaced the system of yore.

Depths of despair

Those who argue thusly usually conflate unregulated “free markets” with political freedom and economic equality. They also assert that capitalism facilitates the rise and fall of deserving or undeserving elites, and that it also encourages an expanding middle class. This proves, they argue, that capitalism can be fair and open. But the rise and fall of a few is by no means equitable or fair; and evidence in leading capitalist countries from the past several decades indicates their middle-class populations are shrinking, particularly as their advantages in the global labor market have eroded. To be sure, workers in the “center,” e.g., the developed world, still benefit from the exploitation of workers in the “periphery,” e.g., the developing world, as Vladimir Lenin observed more than a century ago—but not enough to secure their middle-class position. But this is not the only problem.

Rather, as numerous studies have shown, including Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013), since the early 1980s at least, the U.S. has “saved” capitalism but destroyed the middle class by relaxing financial regulations, decreasing corporate taxes and taxes on the rich, and increasing deficit spending, especially on military and war. Simultaneously, the U.S. undermined unionization, allowed exponential increases in medical and educational costs, and eroded its social welfare system, cutting welfare benefits and even borrowing vast sums from its national pension system to cover current debt payments. It saw negligible investment in infrastructure and innovation, seeing bridges, highways and railways fall into disrepair, and ceding control of technological development to major corporations like Facebook, Google and Apple, among others, who’ve increasingly commoditized consumers’ private lives. Furthermore, wealthy businesses, special interest groups and rich individuals are granted unequal access to policymaking through their political “campaign donations” to members of both political parties. These are legal, but even many Americans see them as “pay to play” schemes—if not bribes—that only guarantee “democracy for the rich.”

Along the way, American workers have endured numerous economic crises, paid incredible fortunes for failed foreign policies and wars, and seen their real wages and economic security decline. Increasingly unable to afford healthcare or higher education, having lost their homes and savings through predatory lending and market bubbles… Many struggle with these longstanding issues accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic. This story has been well-told in part by Anne Case and Angus Deaton in Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism, a bestseller first published in 2020 and updated in 2021—given America’s experience with the pandemic. Both authors are distinguished professors at Princeton University, and the second is a Nobel Laureate in Economics.

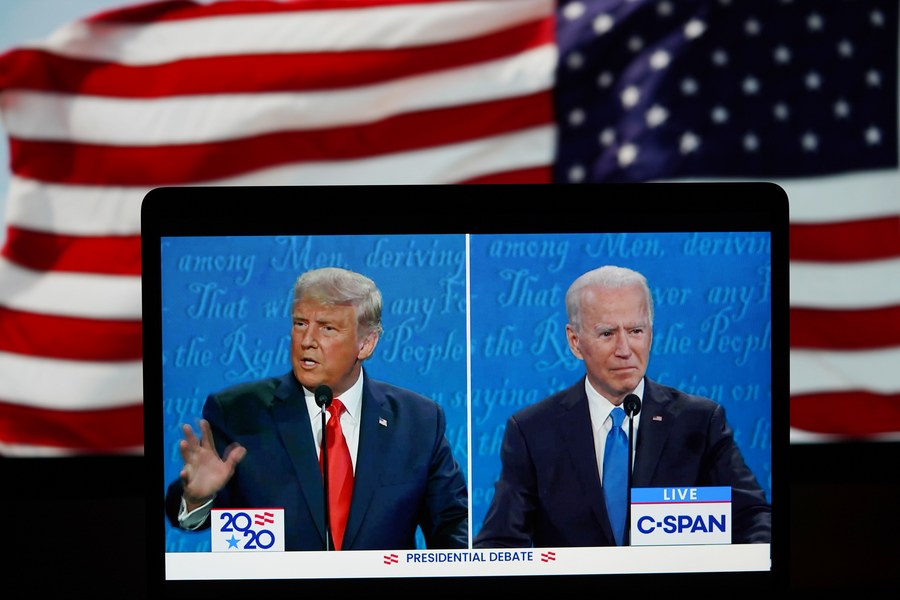

The blame game

It’s well-known that politicians from both U.S. political parties have scapegoated China for the American ills, embracing a trade war and worse, including decoupling and Cold War 2.0. Indeed, this was established in the American imaginary even before the pandemic and has only deepened since, with a tendency to view China in ways that recall the old “yellow peril” and “Red Scare” tropes of the past.

To their credit, Case and Deaton argue that it’s a mistake to blame China for American economic ills. They acknowledge that many U.S. manufacturing jobs were lost to China, but China has also lost manufacturing jobs to others. And one should not discount the fact that lower labor costs have meant lower prices, which have benefited American workers, perhaps even more than offsetting job losses. Instead, Case and Deaton point the finger squarely at the U.S. policymakers who failed to govern effectively and mismanaged the national economy, leaving their citizens and country to be plundered by their own corporations and boom-bust cycles.

And to President Xi Jinping’s credit, increasingly he has emphasized socialist values, including common prosperity, while aggressively pursuing poverty alleviation, rural revitalization and incredibly effective, but very costly, pandemic controls that have put the health and wellbeing of people well-above profits. He has also spearheaded effective regulations of major industries that were accumulating too much power and influence and undermining social and political order. In these contexts, he’s spoken directly about countering the “disorderly expansion of capital,” in a speech at the 10th meeting of the Central Committee for Financial and Economic Affairs on August 17, 2021, an excerpt of which was published in Qiushi, the leading official theoretical journal of the Communist Party of China, two months later. This signaled that social progress in China will indeed be more equitable and socialistic—and guaranteed above all by the state.

This is by no means a shocking development. Xi is the head of a state ruled by a communist party, and he has repeatedly emphasized the importance of Marxism in Chinese development, including its role in China’s goals of achieving common prosperity and developing as a fully modern socialist nation by 2049. Furthermore, although this statement is now refreshed and reemphasized, it’s not entirely new—Chinese leaders of every generation have made similar points since 1949. Yet, more importantly, none of this indicates a new, radical anti-market turn in China’s political economy—far from it. Marxists understand that socially just economic transformations take time. Nevertheless, capitalists are concerned, particularly those in the West, who equate any type of government regulation or social welfare with a “red revolution” despite their own mantras that Marxism and socialism are themselves dead ends.

If the despairing were clearheaded, what would they see? Would they realize capitalism itself is substantially to blame for their problems of inequality, social injustice, climate change and many more, from its earliest days to the present?

The author is a professor of politics and international relations at East China Normal University and a senior research fellow with the Institute for the Development of Socialism with Chinese Characteristics at Southeast University.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +