America’s War Machine

The desire to be a good policeman and to spread democracy around the world has had disastrous consequences for America’s global image and more ominously for the countries that have been destabilized because of the war machine.

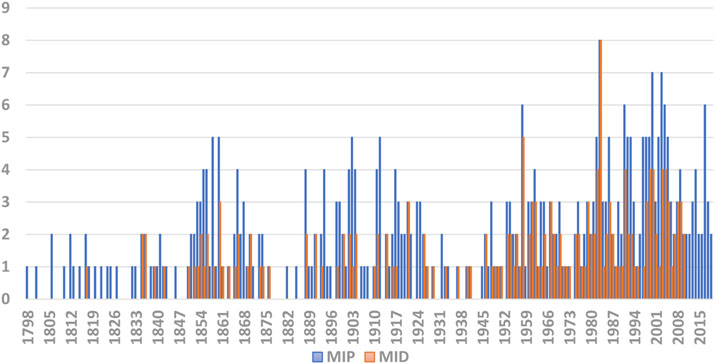

A new academic study, Introducing the Military Intervention Project: A New Dataset on U.S. Military Interventions, 1776-2019, published in the respected Journal of Conflict Resolution (JCR) is an eye opener, and I quote directly from its opening paragraph: “The U.S. has undertaken almost 400 military interventions since the country’s founding in 1776. What is more, these interventions have only increased and intensified in recent years, with the U.S. militarily intervening over 200 times after World War II and over 25 percent of all U.S. military interventions occurring during the post-Cold War era.”

Without a doubt, America’s war machine rages on and on and on, whether the aggression has included direct invasion of another country, covert operations or other acts. It is also likely that the data uncovered by the authors are incomplete; the quoted figure of “almost” 400 could in fact be exceeded.

Keep in mind that the U.S. military has also acted in a particularly aggressive way over the past two decades. According to the study, “Since 2000 alone, the U.S. has engaged in 30 interventions at level 4 (usage of force) or 5 (war).” The authors correctly note that this “militaristic pattern persists during a time of relative peace, one of arguably fewer direct threats to the U.S. homeland and security.”

Put another way, during a period in which the U.S. has been the undisputed world leader in military might, it has been quite active in exhibiting that power across the globe. One analyst, investigative journalist Nick Turse, who also has reviewed the JCR study, suggests the number of post-September 11 reports of U.S. military action is almost certainly lower than the actual figure, partially because of “U.S. government secrecy.”

Building on the work of other researchers, the authors summarize a military intervention as one in which “the purposeful threat, display, or use of military force by official U.S. government channels is explicitly directed toward the government, official representatives, official forces, property, or territory of another state actor.” Covert actions are not going to be as obvious or perhaps as easy to define, but they are part of the U.S. military toolbox and they are used.

The chart below comes from the study, and the blue and red lines represent specific data sets the authors analyzed in order to quantify the lust for war that has existed within the U.S. since its founding 246 years ago. Although the data sets do not always agree on when and where U.S. military engagement happened, they leave little doubt that one U.S. president after another—and especially since the onset of the Cold War—has liberally sent the country’s armed forces around the world.

The authors conclude that two parts of the globe—Latin America and the Caribbean, and East Asia and the Pacific—have been the sites of the most frequent U.S. military action. That fact should intensify the debate about Washington’s reasons for firing up tensions across the Taiwan Straits and inspire even more scrutiny as to whether the Americans would seek a reckless and dangerous engagement with China over the island of Taiwan, which a significant majority of governments around the world continue to affirm belongs to China.

Yes, successive U.S. presidents over the past roughly 50 years have uttered their support for the one-China principle, but American history has also demonstrated an eagerness to send its military to East Asia. The appetite for war in the U.S. might be at a low ebb now after a two-decade mistake in Iraq and Afghanistan and the debacle that was the exit from Afghanistan in August 2021. But we must acknowledge that the beast that is the war machine must be consistently fed. It will soon be hungry again.

This worry over East Asia is further exacerbated when you consider the authors have determined that “the post-Cold War era has seen the U.S. wield its military might toward more missions of democratization, human rights enforcement, humanitarian interventions, and third-party interventions in internal domestic crises across the world.” In other words, for most of its history, the U.S. has primarily equated military adventures to protecting its national interests. But more recently, the concept of being the global policeman has suited the Americans and their allies in the military-industrial complex quite well. There is no reason to believe the eagerness to remain that global policeman will slow down.

Speaking of humanitarian ventures, you would be wise to remember what the authors wrote about such military activities: “Military interventions in Bosnia, Kosovo, Libya, and Somalia all held some humanitarian justifications, but these interventions have typically failed to achieve their humanitarian and democratizing objectives… Instead of spreading democracy, these interventions tend to transform target states into illiberal democracies—at best.”

Or to put it more bluntly, the desire to be a good policeman and to spread democracy around the world has had disastrous consequences for America’s global image and more ominously for the countries that have been destabilized because of the war machine. Iraq and Afghanistan remain crippled because the U.S. believed both were willing to embrace democracy, although the concept had no history in either location.

Every nation on Earth has the right to protect itself from enemies near and far. Sadly, that posture is going to sometimes require sending the country’s military into battle in order to defend domestic norms and values. But the U.S. has averaged roughly 1.6 military conflicts each year. Only the most rabid war-loving, missile-producing and weapons-creating people and corporations would defend such continuous international aggression. War-loving, missile-producing and weapons-creating? Sounds like the military-industrial complex, no?

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +