COVID-19: Why Is Medical System in Metropolises So Vulnerable?

Wuhan was the first to confront the COVID-19 outbreak. Other metropolises like New York and Tokyo are equally vulnerable to the pandemic. It seems that the novel coronavirus is testing the medical capability of all global cities.

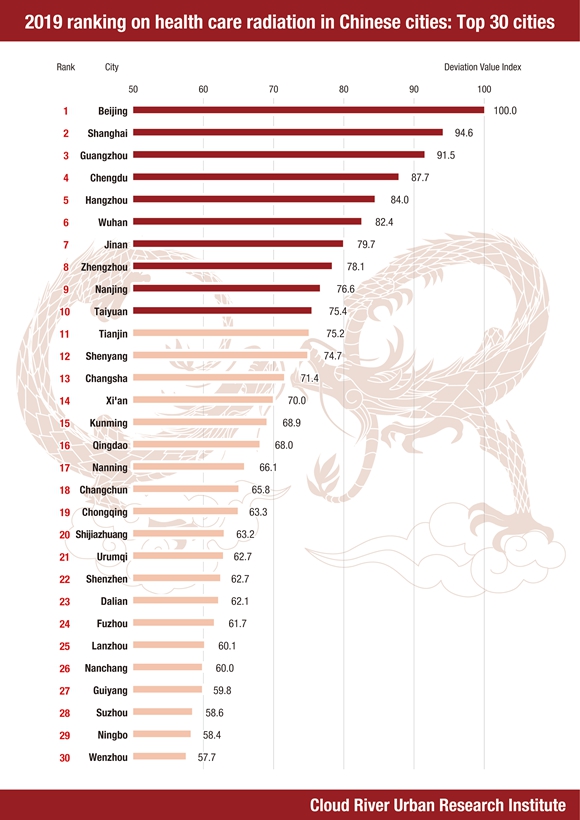

Editor’s note: How come the metropolises around the world with concentrated medical resources are so vulnerable to the COVID-19 outbreak? What is the future of globalization and international metropolises? As the Cloud River Urban Research Institute releases the 2019 ranking on medical care radiation of Chinese cities, Professor Zhou Muzhi gives his perspective on the health care system in major cities in the coronavirus crisis.

As part of the China Integrated City Index, the Cloud River Urban Research Institute has released the 2019 ranking on health care radiation based on a research of 297 cities above prefecture-level across China. The top 10 are Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu, Hangzhou, Wuhan, Jinan, Zhengzhou, Nanjing and Taiyuan. The following top 20 are Tianjin, Shenyang, Changsha, Xi’an, Kunming, Qingdao, Nanning, Changchun, Chongqing, and Shijiazhuang. And the following top 30 are Urumqi, Shenzhen, Dalian, Fuzhou, Lanzhou, Nanchang, Guiyang, Suzhou, Ningbo and Wenzhou.

Evaluating a city’s medical care radiation mainly focuses on the number of physicians and the 3A-grade hospitals. The top 30 cities account for 15% of the certified physicians, 30% of hospital beds and 45% of 3A-grade hospitals in the country. China’s medical resources, especially the best hospitals, are mainly concentrated in cities higher in the ranking, which serve local residents as well as people from all around China.

One would doubt why cities like Wuhan, with one of the top medical resources, can be so vulnerable to the COVID-19 outbreak and even overwhelmed by the influx of patients?How cities should do to prepare for future epidemics?

A test for the health care system

Wuhan was the first to confront the COVID-19 outbreak. The city climbed one place to the sixth in the 2019 medical care radiation ranking, as it boasts 37 3A-grade hospitals, nearly 40,000 physicians, 54,000 nurses and 95,000 beds. It is hard to expect that a city with such strong health care capacity could be overwhelmed by the coronavirus epidemic.

Other metropolises like New York and Tokyo are equally vulnerable to the pandemic. It seems that the novel coronavirus is testing the medical capability of all global cities.

There are three reasons for the breakdown of the medical care system.

First, overloaded hospitals.

One feature of the COVID-19 epidemic is the exponential growth of infections. Especially during the early stage of the outbreak, the surge in infections and social panic have driven a lot of people, whether they were infected or not, to seek testing and treatment in hospitals. This has caused disorder, leaving those who are critically ill unable to receive efficient and quality care. It is also a reason for its high fatality rate. Moreover, the overcrowded emergency rooms, with confirmed cases, suspected patients as well as their families, can also lead to many hospital-acquired infections (HAI).

Italy, one of the hardest-hit countries in the pandemic, has a relatively high density of physicians, counting 4 per 1,000 people, but the country still suffers a breakdown in its health care system. In the Lombardy region, the number of infections has quickly risen from 1,000 on March 2, to over 10,000 on March 14, and to over 40,000 by the end of March. As many patients with critical conditions could not be treated in time, the fatality rate in Italy is as high as 13%. By April 15, there had been 16,000 confirmed coronavirus cases in Italy, and the death toll was 21,000.

The density of physicians in the U.S., Japan and China was only 2.6, 2.4 and 2 per 1,000 people respectively, much lower than that in Italy.

Wuhan has 4.9 physicians per 1,000 people, while the number in the New York state is 4.6 per 1,000, both higher than their national average. However, the medical care system in both places was still overstretched by the outbreak. By April 16, 83.5% of the COVID-19 deaths in China had happened in Wuhan.

Japan’s capital Tokyo has 3.3 physicians per 1,000 people, lower than the level in Wuhan and the New York State. Therefore, the Japanese government has been trying to avoid overcrowded emergency rooms as a key part of its response to COVID-19. The government advises the residents not to go to the hospital and even strictly limits testing to reduce hospitalization. Japan’s measures are so far effective to reduce the number of hospital-acquired infections and lower the fatality rate as the medical resources are mostly given to those with critical conditions. By April 15, Japans’ fatality rate had been around 2%. By April 10, deaths per 100,000 in Japan had been only 0.07, compared to 33.06 in Spain, 30.25 in Italy, 18.25 in France and 5.04 in the U.S. So far, it is fair to say that Japan has avoided collapse in the medical care system through controlling hospital visits.

However, due to the limit on testing, asymptomatic and mild cases could not be quickly identified, isolated and treated, which brings an underlying problem and casts a shadow to Japan’s COVID-19 response. After the announcement of the state of emergency, Japan adjusted its strategy and started to expand testing.

Second, a drop in the number of medical staff.

A drop in the number of medical staff caused by infections also features in the pandemic outbreaks.

In the early stage of the outbreaks, the countries lacked knowledge of the coronavirus transmission, and medical staff faced a huge risk of infection due to the shortage of protective resources such as masks, protective clothing, and negative pressure wards. Those factors made testing, sampling, intubation, and other medical practices that are inherently at risk of exposure even more dangerous. As a result, the countries have seen a significant decrease in the number of medical staff caused by infections, which exacerbated the shortage of medical staff amid the outbreaks and the scramble for medical resources.

According to the information released by the World Health Organization, data reported by 52 countries showed that 22,073 medical workers had been diagnosed with COVID-19 as of April 8. The situation turned out to be even worse. As of April 15, Spain and Italy alone saw 26,672 and 15,000 medical workers infected respectively.

Apart from the risks during the treatment, the extensive isolation and infection resulted from a dinner party of trainee doctors from Keio University Hospital dealt another major blow to the already scarce medical workforce in Tokyo.

The super-transmissible coronavirus has severely threatened the safety of medical staff and weakened medical capabilities, resulting in the collapse of the medical system.

Therefore, it is critical to protect the safety of medical workers during the fight against COVID-19.

Third, a serious shortage of hospital beds.

Since the outbreaks, the countries have experienced a shortage of medical supplies such as face masks, protective clothing, disinfectant, test kits, ventilators, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation machines, and especially, hospital beds. COVID-19 patients are required to be treated under quarantine to curb the spread of the super-transmissible coronavirus, and severe cases should be treated in intensive care units (ICUs), but general hospitals have been in serious shortage of beds.

There are up to 13.1 hospital beds per 1,000 people in Japan, the highest in the world. For Tokyo, a city with a total of 128,000 hospital beds, the figure is 9.3. Even so, it already saw a severe shortage of hospital beds.

In contrast to Tokyo, for every 1,000 people, Italy has a high number of doctors but only 3.2 beds, the U.S. has only 2.8 beds, and New York has only 2.6, even lower than the national average. Obviously, inadequate hospital beds have become a bottleneck that restricts medical institutions from receiving patients and hinders timely treatment.

The figure of China is 4.3, a quarter of that of Japan but higher than that of the U.S. and Italy. Wuhan, in particular, has 95,000 beds, or 8.6 beds per 1,000 people, almost as high as that of Tokyo, but it still suffered from a serious shortage of hospital beds in the early stage of the outbreak.

In fact, the problem is that not all hospital beds are qualified for receiving COVID-19 patients for isolation, and the scramble for medical resources has made the bed shortage even more prominent.

Wuhan rush-built the Huoshenshan Hospital and the Leishenshan Hospital for severe cases under national support. The two hospitals with high isolation levels are equipped with specialized treatment equipment, and 1,000 beds and 1,600 beds, respectively. The city also converted stadiums into 16 temporary treatment centers, and quickly provided 13,000 beds with antibacterial and epidemic prevention levels up to those of first-class hospitals in China. The move channeled mild cases, helped to concentrate high-end medical resources on severe cases, and alleviated the pressure.

The experience of Wuhan—building Huoshenshan, Leishenshan and temporary treatment centers to address bed shortage—is worthy of reference and learning for the world.

Japan now requires some confirmed patients to stay at home for quarantine due to insufficient beds, which is actually an extremely dangerous practice. First, it puts the family members of the patients at risk and may lead to infections in clusters within the families. Second, patients cannot get effective and professional treatment, and without timely update on health conditions, they may not be able to receive swift referral for treatment when the conditions deteriorate.

Therefore, Tokyo is now transforming hotels and convention and exhibition facilities into isolation wards for patients with mild symptoms, in an effort to channel mild cases and relieve the pressure on hospitals. A more serious problem in Tokyo is the shortage of ICUs. Japan has merely five ICU beds per 100,000 people, and there is a huge gap compared with the 35 in the U.S., 30 in Germany, 12 in France, 12 in Italy, and 10 in Spain. Tokyo has only 764 ICU beds, or only 5.5 per 100,000 people. To provide enough beds for severe cases is a key for Tokyo to avoid a potential collapse of the medical system.

The countries have adopted a variety of measures to address bed shortage in affected areas, with the U.S. even sending naval hospital ships to assist. In late March, U.S. President Donald Trump sent USNS Mercy and USNS Comfort hospital ships to Los Angeles and New York, respectively, offering them mobile hospitals on the sea with 1,000 high-class beds each. Though the beds are not necessarily suitable for COVID-19 patients, the hospital ships can alleviate the pressure on general hospitals in beds and leave them more space for treating COVID-19 patients by accepting a large number of patients with common diseases.

The emergency importation of a “hospital” has also become a new option. Struggling with a desperate shortage of beds amid the outbreak, South Korea imported an entire “Huoshenshan Hospital in slabs” from the Broad Group in China. The prefabricated stainless-steel slabs made up negative pressure isolation wards in South Korea. Equipped with fresh air systems and ozone technologies, the wards have the highest level of protection against cross infection. The first phase of the project took only two days locally before the wards were put into use.

From global failure to global fight

Infectious diseases used to be the biggest killer of human beings. For example, the outbreak of Black Death in Sicily in 1347 caused 25 million deaths in Europe over 20 years. The outbreak of Spanish Flu in 1918 killed 25 million to 40 million people worldwide.

With the development and popularization of antibacterial drugs and vaccines over the past hundred years, most of the infectious diseases that once did extreme harm to human health and life, such as smallpox, polio, measles, rubella, mumps, tetanus, pertussis, and diphtheria, are now eliminated or brought under control. The number of deaths from infectious diseases such as pneumonia, gastroenteritis, hepatitis, tuberculosis, and influenza has decreased dramatically in developed countries since the 1950s, and chronic diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases, hypertension, and diabetes have become the main causes of death.

The success in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases has helped to increase the average life expectancy of human beings, but the changes in the main causes of death have prompted the focus of medical systems around the world, particularly in developed countries, to shift from infectious diseases to chronic ones. As a result, countries are now investing too little in the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases, and existing medical resources are mainly concentrated on dealing with chronic diseases.

From the perspective of existing medical resources, neither the medical personnel in terms of professional background, nor the equipment, nor even the entire medical system can respond to the outbreaks in a timely and effective manner. Therefore, even metropolises with rich medical resources, such as Wuhan, New York, and Tokyo, were caught off guard and paid a heavy price in their confront with COVID-19.

Bill Gates warned the world as early as 2015 that too little investment in infectious diseases caused by viruses would lead to global failure. The scourge of COVID-19 unfortunately confirmed his prediction.

(1) Domestic and international aid

To address the shortage of medical workers and massive job cuts in Wuhan, China relies on its strong mobilization ability to send many medical workers across the country to aid Wuhan. The total number of medical workers sent to Wuhan reached 42,000, which largely alleviated Wuhan’s medical stress.

A country’s ability to aid epidemic-hit area is critical to the fight against COVID-19, but not every country has the ability. As evidenced in New York and Tokyo, even developed countries boasting rich medical resources cannot swiftly mobilize enough medical workers to aid the area hit by the epidemic.

What is more worrying is those developing countries suffering from the shortage of medical resources. Not to mention Africa, India and Indonesia in Asia, for example, have only 0.8 physicians and 0.3 physicians per 1,000 people, respectively, with 0.5 beds and 1 bed per 1,000 people, respectively. In those countries with scarce medical resources and poor national rescue capacity, hospitals will be overstretched during the outbreak, which may lead to a severe disaster. Therefore, how to organize the global rescue force is imminent. The problem is that most of the developed countries themselves are now busy responding to the pandemic,paying little heed to others. China’s medical assistance to other countries is particularly valuable at this moment.

(2) Explosive scientific progress

Measures taken by countries, such as declaring a nationwide emergency state, closing borders, city lockdown, home quarantine, and social distancing, are aimed to substantially reduce or avoid personnel exchanges, and block the spread of the virus. Although those measures have taken effect, they cannot completely wipe out the virus. Therefore, even if the pandemic is contained temporarily, the victory we have won is very fragile, and the virus may come back any time.

To secure the victory, we have to rely on the development of science and technology. Since the outbreak, the U.S. has upgraded six generations of COVID-19 test kits in 12 days, as test time has been shortened from two days to one day, then to six hours, then to 3.5 hours, then to 1.5 hours, and then to five minutes, with an accuracy rate above 95%. Cheap, rapid and accurate testing methods will make large-scale screening possible.

Convenient and simple COVID-19 antibody tests have been available in the U.S., so the U.S. government is mulling over the implementation of COVID-19 antibody tests for its entire population. At the same time, the development of wonder drugs and vaccines for COVID-19 is gearing up around the world.

The pandemic is stimulating the explosive progress of related science and technology. Only when we master the three magic weapons — detection, wonder drugs and vaccines, can we truly control and defeat the coronavirus.

Crisis is also a turning point. Each global war and crisis in modern times brought opportunities and an explosive technological revolution. World War II, for instance, promoted the development of the aviation industry, and opened the door of the nuclear industry. World War II not only gave birth to the development of the aerospace technology, but also laid the foundation for the internet technology.

The urgency of the pandemic will not only accelerate technological progress, but also expand the technological path, making unnoticed technological paths stand out. For example, Traditional Chinese Medicine is gaining global attention because of its role in the fight against COVID-19, which may possibly provide a valuable opportunity for TCM to go global.

Ozone is also a technology path that has been ignored due to prejudice. I called for attention to the disinfection efficacy of ozone in an article published on Feb. 18 and advocated the use of ozone in containing COVID-19. Experiments conducted in Japan have proved that the possibility of virus transmission through droplets in a closed environment is 18.7 times higher than that in an unclosed environment. Therefore, an important strategy of the Japanese government to deal with COVID-19 is to call on its people to avoid the confined environment, crowding and close contact. If a breakthrough can be made in the research and development of ozone sensors to control the concentration of ozone as cheaply and freely as we can control the temperature, we are hopeful to solve the problem of virus infection in indoor space and liberate people from the fear of communication by using ozone to sterilize and kill viruses in the presence of people.

The global fight against the pandemic is bound to trigger a huge leap in science and technology and push for industrial upgrade.

(3) Globalization will not end

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, all countries have been cutting off international personnel exchanges and putting cities on lockdown, and thus the globalization comes to a halt immediately. There will be no shortage of worries about the future of globalization, doubts about large-city-oriented urbanization, and even negative voices.

Indeed, with the further development of globalization, international personnel exchanges have expanded rapidly, and international trips sharply increased from 400 million 30 years ago to 1.4 billion in 2018.

Under the background of globalization, urbanization is unfolding worldwide. From 1980 to 2019, 117 cities saw their net population increase more than 2.5 million. During this period, the total net population increase of these cities was up to 630 million. It is particularly noteworthy that the number of megacities with a population of more than 10 million increased from five in 1980 to 33. Moreover, most of these megacities are the centers of international exchanges, and the metropolises that lead the world’s political and economic development. Their total population is 570 million, accounting for 15.7% of the world’s total population.

The highly dense aviation network and frequent personnel exchanges lead to the spread of COVID-19 around the world, leading to the pandemic. Many international metropolises with a large population and intensive international exchanges have become areas hard hit by the outbreak.

However, it must be clearly understood that the real reason for the global spread of the novel coronavirus is not the speed and density of international personnel exchanges, but the long-term negligence of human beings for the threat of infectious diseases.

In fact, the process of globalization has been accompanied by the threat of the spread of infectious diseases from the very beginning. From the age of great navigation to today, human beings have been playing games with infectious diseases, during which they have paid heavy costs. However, because of the big victory against infectious diseases after the Second World War, the developed countries and world organizations have tended to neglect the threat of infectious diseases for a long time.

The Global Risks Report 2020 released by the World Economic Forum, ranked 10 risks that may occur in the future 10 years, excluding the risk caused by infectious diseases. In a separate ranking, infectious diseases took the last place in the 10 risks that would affect the world most in the future 10 years.

Unfortunately, contrary to the prediction of the World Economy Forum, in the beginning of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic dealt a big blow to the human society as a whole in an unprecedented way. t the same time, we are happy to see that the outbreak has pushed the world to pay attention to and invest in virus-infectious diseases, which will definitely lead to an explosive technological revolution and social revolution, and will eventually overcome the threat of viral infectious diseases to human beings, and move toward the global victory.

COVID-19 will not put an end to globalization and metropolitanization, but give birth to better globalization and healthier cosmopolitans after the crisis.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +