Dialogue of Civilizations Along the Central Axis of Beijing

The Beijing Central Axis provides a considerable inspiration for current and future societies, and therefore exhibits outstanding universal values.

As China is going to submit the documents about the Beijing Central Axis’ bid for the World Heritage Site title to the UNESCO World Heritage Center soon, the ancient landscape ensemble is garnering lots of global attention.

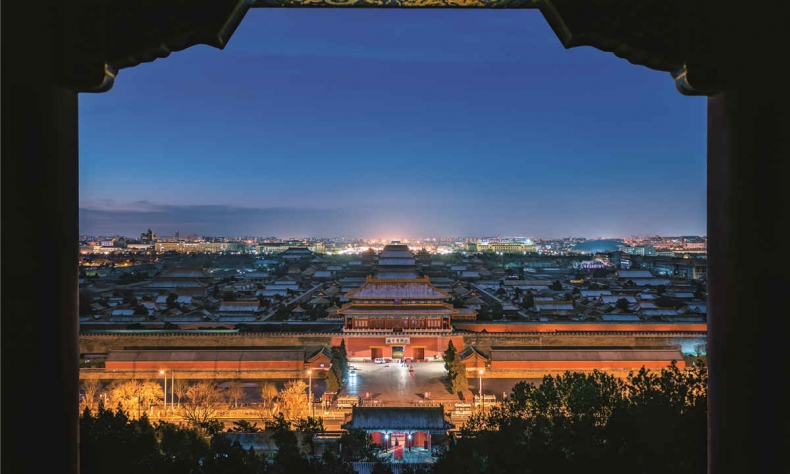

The Central Axis is a 7.8-km line representing the core area of the old city of Beijing. It runs through various landmarks in the capital, starting in the south from the Yongding Gate, connecting the remains of the Imperial Road, Altar of the God of Agricutlure, and the Temple of Heaven, then proceeding all the way to the Zhengyangmen (also known as Qianmen), Tian’anmen Square, the Outer Jinshui Bridge, the Gate of Uprightness, the Altar of Land and Grain, the Imperial Ancestral Temple, the Forbidden City, the Jingshan Hill, the Wan-ning Bridge, and finally to the Drum Tower and Bell Tower in the north.

Beijing alone boasts more than half a dozen sites of “outstanding universal value” inscribed on the World Heritage List, most of them located along the city’s historical central line. But even such an impressive background was deemed insufficient for the inclusion of the Central Axis on the UNESCO list. According to the authorities, fresh work was needed. As a result, a three-year action plan (July 2020-June 2023) was drawn up with dozens of projects involved to better protect the intactness of the ancient axis and accentuate its cultural value per the related international protection regulations on world heritage sites. They encompassed the protection of cultural relics, improving the environment, and managing various buildings. Many traditional Chinese cultural values, like emphasizing centrality and respect for nature, can all find their embodiments in the Central Axis.

Deep foundations

The origin of the Central Axis dates back to the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) when Beijing was known as Dadu. It was further developed during the reign of the subsequent dynasties, and epitomizes Chinese urban life, design, architecture and philosophy.

Its early construction and evolvement overlapped with Chinese explorer and admiral Zheng He’s marathon overseas trips between 1405 and 1433. With 317 ships, it was the largest armada in the world until modern times, sailing through Southeast Asia, Arabia, and eastern Africa several decades before Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama’s expeditions. Zheng He’s armada set a classic example of intellectual exchange propelling civilizational encounters, without conquests or violence. The Central Axis of Beijing also displays inclusiveness and the idea of seeking harmony in diversity which the Chinese culture has valued. As a witness of history and social changes in the ancient capital, the axis has seen China engaged with the world in unique ways. Following its evolvement history, with reference to the country’s modern development and engagement with the rest of the world, you can detect the consistency and the long-lasting charm of Chinese culture and governance ideas.

Bridging civilizations

Currently, none of the other major world capitals possess a central axis that is the accumulation of centuries of civilizational encounters and dialogue of civilizations, including high diplomacy, except perhaps Vatican City. The Forbidden City had an extensive influence on the cultural and architectural development in the rest of East Asia. Envoys from what is today Southeast Asia and Central Asia felt that centrality irradiating from Beijing when they arrived there. There are records of Beijing mandarins receiving highly skilled intellectuals and diplomats from Korea and Japan who could read and write classical Chinese, a tradition formed in their own countries after picking the language from China before the end of the first millennium.

The European intellectuals who best captured the multifaceted Chinese civilization were those who visited the Forbidden City, such as the Italian missionary Matteo Ricci and Spanish priest Diego de Pantoja, who lived in China in the 16th and 17th centuries respectively. Both Ricci and Pantoja could speak and read Chinese. These Western pioneers of Europe-China dialogue between civilizations lived as Beijingers, moving back and forth along the axis. A few centuries later there was U.S. journalist Edgar Snow, who first told the outside world about the Long March of the army led by the Communist Party of China in his classic Red Star Over China, published in 1937. He became part of China’s history in a historical photograph taken at the Tian’anmen Gate Tower, where he stood with Chairman Mao Zedong on October 1, 1970, the 21st anniversary of the founding of the P.R.C. Both Snow and Ricci are remembered in different locations a few miles away from the Beijing Central Axis, with inscribed gravestones.

Other eminent persons living in the proximity of the Central Axis included Nobel Literature laureate Bertrand Russell, who was a professor at Beijing University. Enthralled by Chinese philosophy and the unique urban layout surrounding him, Russell wrote in 1921: “When I went to China, I went to teach; but every day that I stayed I thought less of what I had to teach them and more of what I had to learn from them.”

Another Nobel laureate, Chilean poet Pablo Neruda, who was one of the founders of the Chile-China Cultural Association in 1952, lauded China’s centrality. George N. Kates, the U.S. sinologist with one of the deepest roots in European culture, wrote The Years That Were Fat: Peking, 1933-1940, an in-depth cultural description of his years in the old imperial city. He is regarded as being the first contemporary Westerner to spread word in the West on the Yuan Dynasty origin of the Beijing Axis.

French intellectual André Malraux also deserves a line here as a connoisseur of East Asia’s philosophy. His example, again, shows how much culture can do when it comes to contributing to mutual understanding among nations. He was the key person President Richard Nixon consulted in the West before going to China to meet Chairman Mao and renew China-U.S. relations. For the meeting, the American delegation entered the Zhongnanhai compound from Chang’an Avenue, which forms the city’s main east-west axis.

If you visit the Beijing Hotel along Chang’an Avenue, also close to the capital’s classic architecture backbone, you can probably still see photos of top politicians’ and technocrats’ delegations from Moscow or New Delhi or various non-aligned countries who visited the capital in the 1950s. It was a time of hope for countries of Asia and Africa in their decolonization processes. The 50s and the 60s were also the time when Beijing was about to get its subway, encircling the most central parts of the axis.

More than an open-air museum

When I was studying at Peking University in the 1980s, I visited the National Museum of China located at the east side of the Tian’anmen Square. A teacher who was a Chinese history savant took time to accompany me and explain how he understood China’s heritage. A month after our meeting, he mailed me a set of historical almanacs, which he hoped would help improve mutual understanding between us. Indeed, culture as a creative result of the human development can inspire people from all continents and contribute to cross-cultural fertilization. The National Museum of China, as part of the Tian’anmen Square complex, is one of the milestones along the Beijing Central Axis.

The bid of the Beijing Central Axis for UNESCO World Heritage Site is globally meaningful. The official application states, “It provides a considerable inspiration for current and future societies, and therefore exhibits outstanding universal values.” The Chinese dream to realize the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation entails reviving the core cultural values of the ancient nation, which have been cherished and passed on for millennia. The Central Axis of Beijing is a classic and representative expression of such cultural values, deserving a deep exploration for people who are truly interested in the country and its cutlure.

Augusto Soto is director of the Dialogue with China Project.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +