Don’t Draw the Wrong Conclusions from “American Factory”

The worst conclusion to draw from “American Factory” is to restrict Chinese investment in American industry.

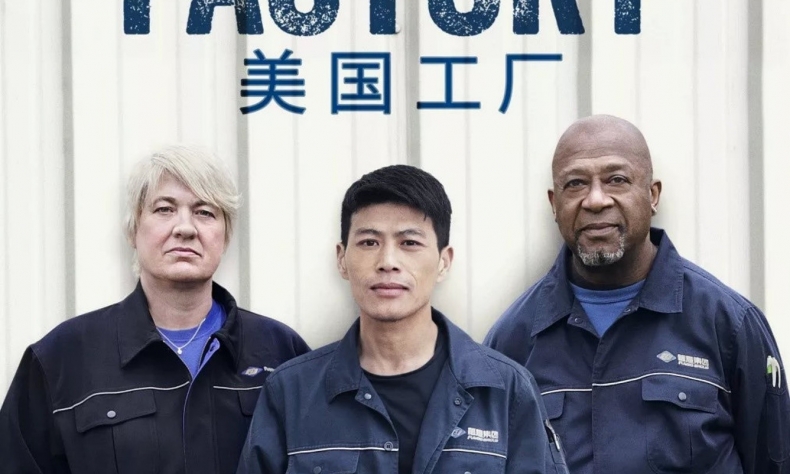

The recently released documentary film “American Factory” by Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar is another one in the genre of films that are aimed at depicting the life and the trials of the American working class and the travails of modern capitalism. Reichert has done a number of these films, but “American Factory” has gained a greater amount of notoriety because it depicts a Fuyao auto-glass factory in Ohio which was set up by a Chinese entrepreneur, Cao Dewang, on a site of a closed General Motors assembly plant, hiring many of the American workers who had been laid off from their GM jobs after the 2008 financial crisis. The film, already in production, also caught the eye of Barak and Michele Obama who have set up a production company to produce documentaries on Netflix, giving it more notoriety.

The film depicts the development of the project through time, noting the excitement of the local workers who could now find employment, although at much lower wages than GM was able to pay them. Cao had also brought a good number of Chinese workers to train the Americans in their glass technology. As it develops, the film depicts the inevitable culture clash between the American and the Chinese work culture, some of the dissatisfaction of the employers with what they feel is the more casual work ethic of the American laborers, and the attempts by the UAW to unionize the workers at the plant. The film also indicates the concerns of the American workers when Cao begins to replace workers with robots in a cost-cutting measure, an automation phenomenon that American workers have been well acquainted with over the last few decades.

What’s Behind the Film?

Due to its one-sided narration of the factory, highlighting cultural differences while ignoring the benefits to local workers, the film, in one sense the film will no doubt contribute to a sense that Chinese investment in U.S. manufacturing is something to be avoided, and in that respect, the movie has a decidedly anti-China thrust. And that is probably the reason it attracted the interest of the Obamas, who have never shown any great appreciation of China or Chinese investment, having frowned upon China’s Belt and Road Initiative when he was president. But that probably is not the reason the producers made the film as they began the project when there was still a good deal of enthusiasm for the new factory in Dayton. And in that sense, the film probably has some lessons to be learned with regard to what is the new phase of globalization.

Undoubtedly, there is often a cultural divergence when a Chinese entrepreneur sets up shop in the U.S., particularly when Chinese investors are not well-acquainted with the American scene or American workers. But as we have seen with similar cultural clashes which have occurred in the context of China’s Belt and Road Initiative in Africa and other countries, time and experience can do much to create a “learning curve” to overcome that clash – on the part of both parties. But ignoring them can only lead to more difficulties. There were similar problems in the 1970s when Japan began major investment in the United States, but the success of Japanese firms in the U.S. like Toyota and Kawasaki proves that patience and growing insight about these issues can lead to success.

China’s Haier refrigerator factory in South Carolina has been a very successful case over decades, admired by both the American workers and the local government. Similar cases of Chinese investment in the US can be found as well. But the documentary seems having no interest in those facts, only highlighting the problems. There are also cultural clashes or problems in American invested factories or companies in China. But China has been trying to solve them, and never depict the American business in a negative way.

The film also notes some of the close personal relationships that were developed between one Chinese worker and his American counterpart, indicating the bonds of friendship created between the two in spite of their different work ethic and work culture. And this exposure of American workers to China and Chinese customs is an important element in those vital people-to-people exchanges that are part and parcel of creating a trusting relationship between our two nations. In addition, there is something to be learned for American workers in some of the practices that have become a mainstay of Chinese production. After all, you have the example of what was a relatively poor country several decades ago jump to the top of the charts in production and in technological advances in a very short period of time. There must also be lessons here for the American economy to learn, or in some cases, to relearn, as many of these practices were once a part of the American fabric of production.

Who is Closing the Door?

The worst conclusion to draw from “American Factory” is to restrict Chinese investment in American industry. We cannot return to some “Fortress America” thinking in dealing with the problems of what is really a new stage in globalization. America has to remain open to trade and to investment from other countries if we are to rebuild our productive capabilities and improve our people’s dwindling standard of living. China will not become a “savior” of U.S. production, but at the same time Chinese investment should not be demonized, as we are tending to do today. We cannot ignore that China keeps its door open to companies from the U.S. and the rest of the world under the circumstance that Trump administration is imposing more tariffs on Chinese imports and continuing the trade war that the end can’t be seen. Compared with the U.S., China is more confident to embrace a globalized world today.

When a Chinese Railway company builds a plant in Massachusetts to help rebuild the Boston subway system or to produce for the first time high-speed rail transportation on the American continent, this will be a major contribution in our effort in rebuilding our crumbling infrastructure. And if a Chinese entrepreneur like Cao Dewang wants to take a chance on setting up their operations on U.S. soil and to deal with the new cultural environment which that entails, they should be encouraged to do so and not denigrated for their efforts. We should maintain an “open door policy” to Chinese trade and Chinese investment. We continue to control the terms of that trade and that investment as do all sovereign trading nations. But to try to shut the tap on what can help “Make America Great Again” will only lead us further down a slippery slope. The U.S. trade dispute with China has already led this year to a decline of foreign direct investment and venture-capital deals between China and the U.S. by 18%. And this also means lost jobs for American workers. If the trade dispute continues unabated and tensions between the two countries remain at a high level, we will only see fewer jobs and higher prices for American workers.

Editor: Liana

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +