How will China Prove the Western Media Wrong?

It is hard work to gain a full understanding of Xi’s report. But there is a much easier way. Read The Economist’s coverage of the congress, which is considerably shorter in length, and bet on the opposite being true.

By Eric Li

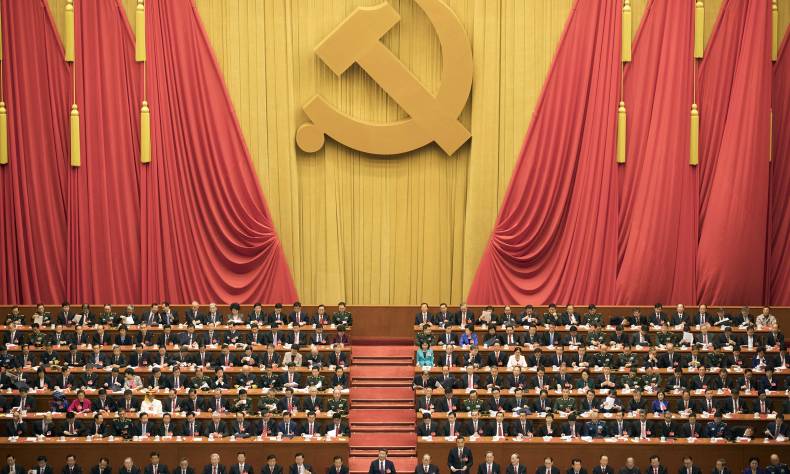

On October 24, both the The Washington Post and The Huffington Post published a review article—Western media is still wrong. China will continue to rise.—about the 19th CPC National Congress. It was written by Eric Li,a columnist of The World Post, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.“As the 19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China draws to a close,” he wrote, “analysts are parsing through President Xi Jinping’s 30,000-plus-word report — delivered in a three-and-a-half-hour address without breaks — to decipher the direction of the most populous nation in the world…”

Meanwhile, some foreign media were stirring things up, querying many of China’s achievements.

It is hard work to gain a full understanding of Xi’s report, especially considering the substantial content in terms of grand blueprint and detailed policies.

“But there is a much easier way,” according to Li. “Read The Economist’s coverage of the congress, which is considerably shorter in length, and bet on the opposite being true.”

So let us follow his advice, and take a look at what is The Economist has had to say.

- The 14th CPC Party Congress was held in October 1992. The Economist editorial view was that the party had “stepped backwards”. It characterized the socialist market economy which the congress proposed as an “oxymoron.”

- During the 15th Party Congress in 1997, the magazine described the goals which the congress set as “hollow promises”. It opined that raising expectations and then dashing them would be “a recipe for civil strife” in China.

- Five years later in 2002, during the 16th Party Congress, The Economist made ominous noises about “crisis” and “unrest”. It believed that the “familiar policy of trying to muddle through” could no longer be used to deal with urgent problems.

- Another five years pass. The same magazine now claims that “Politically, little has changed”, expressing dissatisfaction at the lack of reform during the 17th Party Congress.

- During the 18th Party Congress, The Economist became a little unhinged. Quoting an “anonymous source”, it claimed that China was unstable at the grassroots, dejected in the middle strata, and out of control at the top”.

- This would duly be outdone by this year’s cover, which warned the world “not to expect Mr. Xi to change China, or the world, for the better”.

When the magazine said China had “stepped backwards” in 1992, this was precisely the year of Deng Xiaoping’s now famous southern tour that launched a new wave of reform, the likes of which the world had never before seen. The “muddling through” years between 2002 and 2012 saw China’s GDP quadruple and its economy become the world’s largest by purchasing power parity (PPP).

Between 2012 and 2017, historic changes took place in the country as a whole. The country’s GDP rose from 54 trillion to 80 trillion yuan (8.2 trillion to 12.1 trillion U.S. dollars).

Today, by several measures, China is the most powerful economic engine in the world. Per capita income is approaching $10,000. It is a burgeoning entrepreneurial society that has created some of the largest companies in the world. China has led improvements in health, education, science and overall standard of living at a speed and scale that is unprecedented in human history.

It is at this historic junction that the current party congress was held. Delivered at the outset of the congress, Xi’s report includes 13 sections, each divided into numerous parts, covering in considerable detail issues including housing, health, science, defense, artificial intelligence and the sharing economy. Beyond that, the party presents a roadmap for a new 30-year journey to realize the Chinese dream of national rejuvenation— the plan for a new era of socialism with Chinese characteristics.

From the report, we can see that Xi’s plan can be broken down into the following five main points.

- The Economy

Xi projects the basic realization of socialist modernization by 2035, resulting in a major expansion of the middle class, with continuing growth through 2050. In the Chinese political lexicon, this means becoming the economic and technological equivalent of a developed nation. In per capita GDP terms, this would imply up to three times the current level, to between $20,000 and $30,000. At this level of performance, China will formally surpass the U.S. in overall GDP aggregate well before 2035.

- Sustainability

Xi made the point very clearly that the primary stress-point in Chinese society has now shifted from underdevelopment to imbalanced development and sustainability. It calls for a concentrated drive to eradicate poverty, as the increasing wealth gap resulting from rapid development is the enemy of long-term sustainability.

In the five years since the 18th Party Congress, at least 60 million people have been lifted out of poverty. If this rate is sustained, the tens of millions still living below the poverty line will all be lifted out of poverty in only a few years by 2020.

The environment is, of course, the other threat to sustainability. Xi maps out major structural changes to the economy and energy usage and envisions a substantially cleaner environment in two decades.

- Anti-corruption

Five years ago, corruption was seen as the biggest threat to the Party’s hold on power. The 18th Party Congress then undertook a strict anti-corruption campaign, of a breadth and depth that few had anticipated.

The anti-corruption campaign has been one of the hottest issues and a key focus in the past five years. According to the latest data published by the Central Discipline Inspection Commission on Oct. 19, the CCDI has examined more than 2.67 million items of evidence of possible corruption, filed and investigated more than 1.55 million cases, and punished nearly 1.54 million officials. With such strict execution of discipline and such a rigorous anti-corruption campaign, the growth in corruption has been effectively curbed.

- China’s New Image on the International Stage

For the rest of the world, China is coming to a theater near you. With the great initiative of Belt and Road Initiative, China is bringing its considerable experience and capacity in infrastructure-led economic development to a vast number of developing and developed countries alike.

China’s active engagement with the world is based on a qualitatively different proposition than the one championed by the West in the recent past. Instead of a universalist approach seeking to standardize the world with the same set of neoliberal economic and political rules and values, Xi advocates a new version of globalization under which increased interconnectedness does not come at the expense of national sovereignty. He calls for a global “community of common destiny” but one that fosters a competition of ideas, which — given the trouble globalization is in — makes sense.

- A New Narrative for a New Era

With the 19th Party Congress, Xi is formally launching a project to provide a new narrative to current events. The prevailing theories that have guided the world’s thinking about the rise and fall of nations no longer make sense. If elections and privatization are the prerequisites to development, why has China succeeded without them, while so many others have failed after taking these prescriptions?

In the past 30 years, China has effectively combined socialism and the market economy. In other words, what The Economist called an “oxymoron” has become an extraordinary success. But how? No leader in the history of the People’s Republic has placed so much emphasis on the importance of Chinese traditional culture as Xi. And yet he is adamant in his determination to preserve a Marxist outlook in modern China.

Can we weave together a coherent narrative that absorbs modern Marxism into 5,000 years of China’s heritage? China has actually done it before, by absorbing the foreign culture of Buddhism into its Confucian cultural polity more than a millennium ago. That process took more than a hundred years. And now it has been more than a century since modern Western ideas, including Marxism, first began to influence China.

Paradigm shifts in fundamental narratives take a very long time, and China’s is only at its formative stage. Xi seems determined to accelerate the initial phase of this project. He calls it the “sinicization of Marxism.” The exploration of ideas that this entails may be China’s most significant contribution to the 21st century. Not since the European Enlightenment has the world been so hungry for new approaches.

All in all, the party’s ability to adapt to changing times by reinventing itself is extraordinary. China does not have multiparty elections — the leadership of Chinese Communist Party is the core of China’s political system. All indications at this point are that it has strong vitality.

The Economist is not alone. It is more or less representative of Western media coverage of arguably the most consequential development of our time: the Chinese renaissance. Given the track record of the party, we believe that China will continue to prove The Economist wrong. Xi Jinping will indeed “change China, and the world, for the better.”

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +