Queen Elizabeth II and China

For Britain and China during Queen Elizabeth II’s long time on the throne, despite often huge challenges and great difficulties in the bilateral dialogue, the two sides never stopped talking to each other.

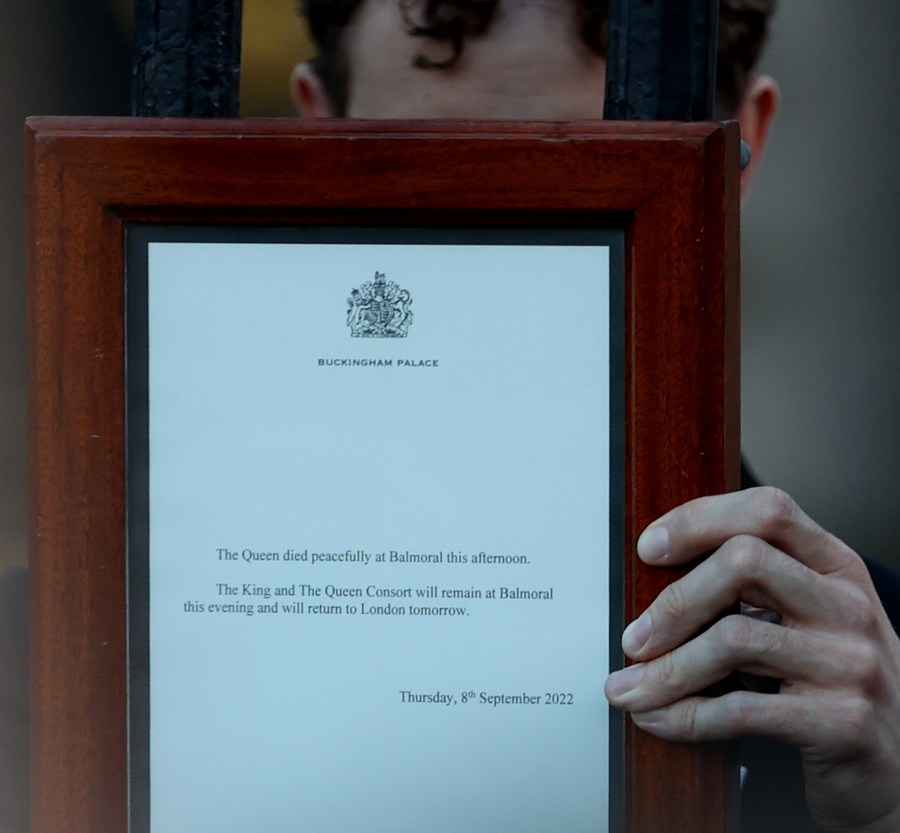

The passing of Queen Elizabeth II on September 8, after a reign of over 70 years, brought to the end an extraordinary life, and an era in British and European history. Queen Elizabeth II came to the throne on the death of her father King George VI in February 1952 when Winston Churchill was prime minister. She died only days after appointing the 15th incumbent to this position, Liz Truss. Churchill was born in 1874, and Truss in 1975. There is a gap in the birth years between the first and last prime ministers who served the Queen of 101 years. This is one of many utterly extraordinary statistics about her reign.

Queen Elizabeth II was a much traveled monarch, and indeed the first British head of state to visit China, in 1986. She also visited Hong Kong a decade before this in 1975, when the Chinese territory was still under British colonial control.

Ties during the Elizabethan era

On January 6, 1950, Britain became the first major Western country to recognize the newly founded People’s Republic of China (PRC). This happened largely through recognition of the need to continue having links with China because of British interests in Hong Kong and the wider region. This recognition attracted great criticism from the U.S., and was made even more complicated by the Korean War, to which Chinese volunteers in significant numbers went to fight, which started in late 1950. But it was a recognition Britain never stepped away from.

Almost from the very start of the late Queen’s reign, China figured as a uniquely important, but complex, partner, and one with which Britain enjoyed a historically important but challenging relationship. While the post-World War II era saw Britain’s global role greatly change and in many ways reduce from what it had been before this, the country still had major trade and commercial interests in Asia. In China, it was the desire to try to preserve these as much as possible that meant a diplomatic mission was maintained in Beijing.

The intensification of the Cold War, and the pressure in particular by allies of Britain such as the U.S., meant that by the mid-1950s, most of the foreign-owned businesses located in the Chinese mainland had either closed down or moved to Hong Kong. Some companies like Royal Dutch Shell did maintain at least some presence. A delegation of business people who had made linkages with Chinese partners through a trade mission sent to Moscow, the Soviet Union, in 1953 did manage to undertake a number of trade visits to China. And figures as diverse as the Dean of Canterbury Cathedral and the poet Edmund Blunden were able to undertake visits to China in the first decade or so of the PRC. But global political conditions meant that by the late 1960s, there was little sign of Britain finally being able to upgrade its representation to ambassadorial status.

All of this changed dramatically with the restoration of the PRC’s lawful seat in the UN in 1971 and U.S. President Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972. Under Prime Minister Edward Heath, Britain established full diplomatic relations with China, and greater contact happened between the two sides. A major exhibition of Chinese artifacts was held in London in 1972-73, and bilateral political, cultural and economic visits started. All of this only gathered pace after China launched reform and opening up in the late 1970s.

Britain and China had managed to sign an accord in 1984 on the arrangements for the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty. After so much negotiation and discussion, it was felt that a major diplomatic event needed to occur to celebrate the significance of this achievement. Queen Elizabeth II therefore visited Beijing, where she met Deng Xiaoping and other Chinese leaders, and then Xi’an of Shaanxi Province, where she was able to see the Terracotta Warriors. For countries that had had contact with each other for many hundreds of years, this was a poignant moment.

Among her many roles, Queen Elizabeth II was Britain’s most important diplomat, and the face of the British nation. She was well known, not least because in 1999 she was able to host the first ever state visit by a Chinese leader to Britain—President Jiang Zemin. She repeated this for his successor, Hu Jintao, in 2005, and then for Xi Jinping, the current president of China, in 2015. Each of these visits were regarded as a success, and each of them saw the British and Chinese understand more about each other, and develop their relationship in different ways.

Persistent influence

For a leader who was in position for so long, and who provided so much continuity and reassurance, it is hard to imagine clearly what a post-Elizabethan era will look like. King Charles III has of course been preparing for the day he might succeed her for many years. Even so, the unique place she held in British people’s affections and the respect accorded to her work ethic and her sense of duty and dignity will be an impossible act to follow.

For Britain and China during her long time on the throne, despite often huge challenges and great difficulties in the bilateral dialogue, the two sides never stopped talking to each other. Even in the depths of the Cold War, when there was so much division and lack of trust, Britain and China maintained at least some connection. Diplomats from both sides continued to be posted in each other’s capitals.

In later years, many hundreds of thousands of Chinese tourists and students were able to visit Britain. Many of these had a chance to visit places strongly associated with the Queen, from Buckingham Palace to the Tower of London where the Crown Jewels are held. They too could appreciate at least something of the role that she had played in national life, whatever the specific political opinions of individuals. For the vast majority of British people, they had never known any other monarch but Queen Elizabeth II. The day of her death therefore marked truly the end of an era.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +