Still More Questions Than Answers in Fukushima Nuclear Contaminated Water Release

You cannot guarantee our safety. So, stop releasing the nuclear contaminated water.

The standoff between Japan and the countries that are concerned about the release of nuclear contaminated water from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant now resembles a game of table tennis. Of course, the results of a table tennis match are not likely to have any effect on global health. But when water containing a radioactive substance that cannot be destroyed is flushed into the Pacific Ocean (and might be for three decades), major health issues could follow.

First, a brief history lesson: In 2011, an earthquake and then a tsunami crippled the nuclear plant at Fukushima. The plant’s cooling system was corrupted, and the reactors’ cores began to overheat. Clean water was continuously poured to ensure that no further damage was done. Instantly that clean water became radioactive. It has been stored in huge tanks that now need to be emptied so that the complete decommissioning of the facility can take place.

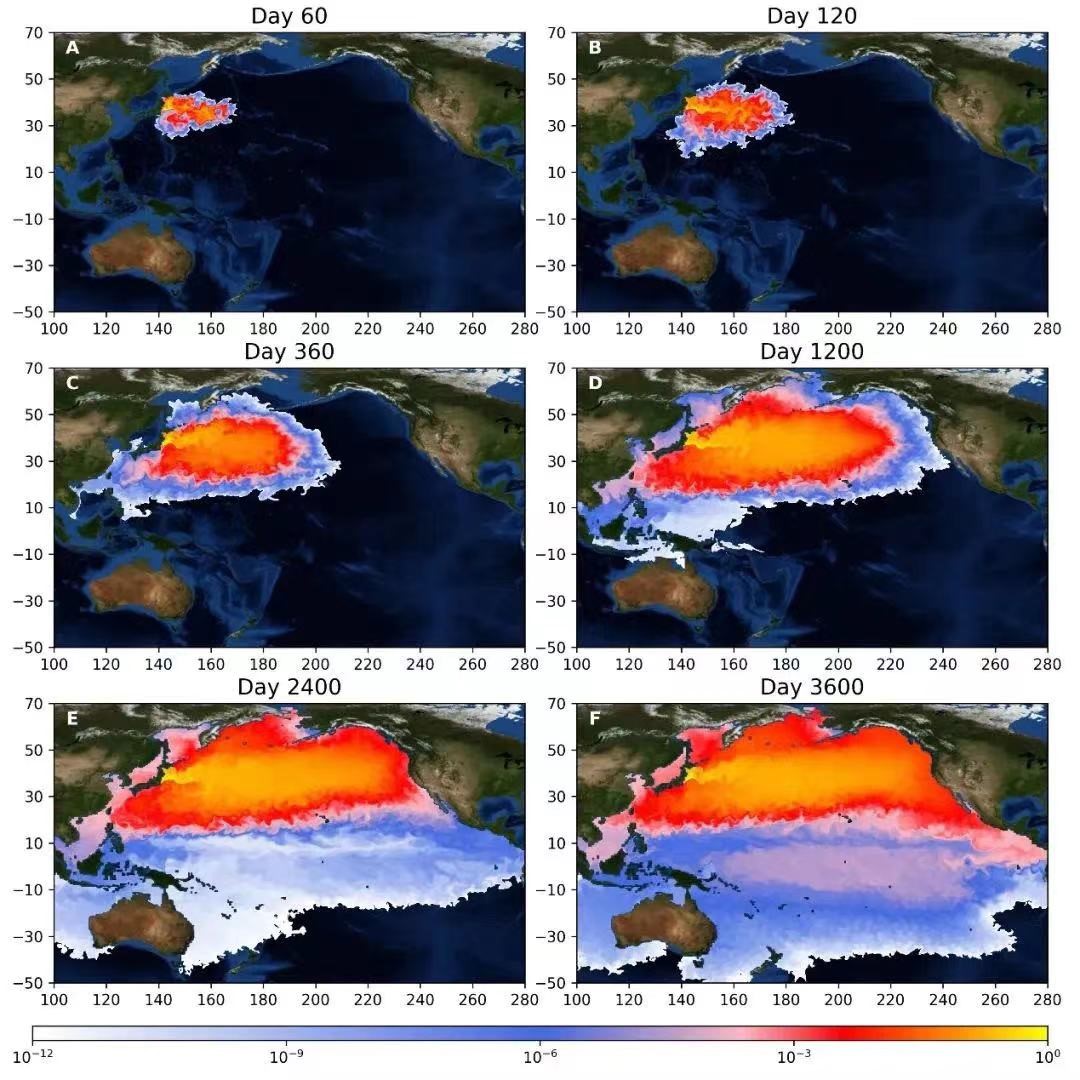

So, what is the plan? It seems so simple: Slowly drain the large tanks that house roughly 1 million metric tons of radioactive water into the massive Pacific Ocean, which presumably is capable of swallowing up the bad water before any of it can cause harm. Japanese officials insist the idea will work and will be safe, and they point to the endorsement by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) for the scheme.

Of course, such a plan cannot be simple. In fact, it could turn out to be incredibly dangerous. The concern is that all of that water contains tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. What can tritium do to the body? According to the Canadian Nuclear Commission, “It can increase the risk of cancer if consumed in extremely large quantities. Tritium can enter the body through inhalation, ingestion or absorption through the skin.”

Cancer can kill. It can ruin lives and families. But, hey, slowly releasing it into the ocean should be fine, right? No one should worry, right? Of course, they should, and that explains why protests throughout East Asia have been so vociferous about this potentially reckless plan.

The scientific community agrees that the ingestion of tritium at low levels should cause no bodily damage. But, as one leading U.S. scientist said to the BBC, “The challenge with radionuclides (such as tritium) is that they present a question that science cannot fully answer; that is, at very low levels of exposure, what can be counted as ‘safe’? One can have a lot of faith in the IAEA’s work while still recognizing that compliance with standards does not mean that there are ‘zero’ environmental or human consequences attributed to the decision.”

“What can be counted as safe?” Those words explain why voices of protest are being heard inside and outside Japan, with some of its closest neighbors being the most upset. One such protest took place over the weekend in Seoul, where environmental organizations are demanding that all possible dangers be eliminated before any further water discharge takes place. Another protest took place outside the Japanese Prime Minister’s residence in Tokyo. Another one took place in the Philippines. These protesters in South Korea, Japan, the Philippines and elsewhere are young and old, rich and poor, and they are all saying the same thing: You cannot guarantee our safety. So, stop releasing the nuclear contaminated water. Now.

Japanese fishers are worried about their economic livelihoods, because the release of nuclear water will harm the reputation of Japan’s seafood products. China has announced that no fish caught off Japan will be allowed into China soon after Japan started the release action on August 24. That wise decision has already led to a sharp decline in fish prices, and one Japanese fisherman has stated bluntly that “catch from the area won’t sell.”

For now, Japan is not budging, and it is not yet clear what kind of aid plan might be put in place to assist the fishers who lose their jobs. They are the first to suffer. Will they be the last?

And, yet, Japanese officials persist, perhaps because the United States remains a steadfast supporter of the water-release plan. Of course, when one recognizes that Fukushima is more than 8,000 kilometers from San Francisco, one of the U.S. west coast’s major cities, it is rather easy for American officials to give a thumbs-up to what is taking place. Remember, whatever health effects result from this controversial plan, they will not be seen in America. Rather the host of nations up and down East Asia are going to bear the health toll, the economic toll, and the social toll.

The article reflects the author’s opinions, and not necessarily the views of China Focus.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +