Trump Trade Balance Goal Fails

The latest U.S. official trade data shows that its global goods trade deficit reached $404.04 billion in H1 2018, up $26.5 billion over a year ago.

By He Weiwen

The latest U.S. official trade data shows that its global goods trade deficit reached $404.04 billion in H1 2018, up $26.5 billion over a year ago. For all of 2017, its deficit expanded by $59.38 billion. As a result, the U.S. global trade deficit increased by $85.88 billion during the 18 months of Trump’s presidency, wiping out the entire deficit cut ($79.41 billion) achieved during the eight years Barack Obama presidency. Hence, President Donald Trump’s repeated promise and efforts to cut the trade deficit has ended in total failure thus far.

Deficit Expansion Is the Inevitable Result of Economic Strength

The U.S. economy picked up during the first half of 2018, with the GDP growth rate hitting 4.1 percent in Q2. Industrial production also accelerated. The total industrial production index went up 6 percent year on year, leading to a strong import growth. According to U.S. Department of Commerce statistics, U.S. imports in goods grew by 8.8 percent year on year in H1 2018, reaching $1233.91 billion, 1.7 percentage points higher than the growth rate in H1 2017, which was 7.1 percent. Production increases were especially strong in Q2 in energy (up 16.4 percent), selected high-tech sectors (up 10.2 percent), computer and peripherals (up 16.4 percent in Q1 and 8.2 percent in Q2), and semiconductors and modules (up 15.3 percent). Accordingly, imports were especially strong in chemicals (up 16.2 percent), machinery (up 13.9 percent), oil and gas (up 12.0 percent), primary metals (up 12.0 percent), electrical equipment and appliances (up 8.4 percent), and computer and electronics (up 7.3 percent). Imports were relatively weak in these sectors, where production grew slowly or even declined. Production of auto and auto parts grew sharply in Q1 (up 14.9 percent), only to fall drastically in Q2 (down 9.1 percent). As a result, imports of transportation equipment increased by only 2.9 percent in H1 2018.

The past trajectory of the U.S. trade deficit’s rises and falls shows that it has a strong positive linkage with the strength of industrial production and the economy at large. U.S. industrial production surged from 1992 to 2000, with an aggregate growth of 52.8 percent within these eight years. In addition, the U.S. global trade deficit quadrupled in the 1990s, from $111.04 billion in 1990, to $452.41 billion in 2000. During the 2008-2009 global financial crisis and economic recession, U.S. industrial production fell by 17.9 percent and the U.S. global trade deficit also shrank from $816.20 billion in 2008 to $503.58 billion in 2009, down $312.62 billion or 38.3 percent.

Hence, to cut back the current trade deficit, the United States needs a recession. In view of the current strength of the U.S. economy—with the aftermath of the trade war still to be felt over time—the U.S. trade deficit is most likely to increase further in the second half of the year.

Deficit Expansion Does Not Mean “Unfair Trade”

The Trump administration accuses the leading trade surplus countries or areas of “unfair trade” for the huge U.S. trade deficit. Therefore, it has resorted to tariff measures on China, the European Union, Japan, Canada and Mexico, in a futile attempt to bring down its deficit. This is totally absurd logic.

According to this rationale, since the U.S. trade deficit means a loss for the United States, then the U.S. trade surplus should mean a gain for the country. During H1 2018, the United States had a global trade deficit of $48.75 billion in oil and gas, but had a surplus of $5.4 billion with China. Therefore, if the world is “unfair” to the United States, then it is “unfair” to China. The United States is “unfair” to the world in agricultural products since it has a chronic trade surplus in this sector worldwide. In transportation equipment, the United States had a deficit of $67.25 in autos and $31.65 billion in auto parts, but a surplus of $5.51 billion in auto bodies. Hence, the world is “unfair” to the United States in auto and auto parts, but it is “unfair” to the world in auto bodies. In the aerospace sector, which is a part of transportation equipment, the United States had a global surplus of $42.43 billion. Again, this is then “unfair” to the rest of the world.

According to the same logic, tariff measures are needed to adjust the imbalances. Thus, the world should impose tariffs on U.S. aerospace and agricultural products, the United States should impose tariffs on auto and auto parts, but the world should impose tariffs on U.S. auto bodies. China should impose tariffs on U.S. auto and auto parts since the latter had a surplus of $2.25 billion. Is there such a ridiculous “fair trade” system?

A trade imbalance has nothing to do with fair trade. The reason for a trade imbalance is simple. International trade is an exchange of goods and currencies across borders. In the case of China-U.S. trade, the United States imported $505.6 billion worth of goods from China in 2017, according to its data. That means that China provided $505.6 billion worth of goods and the United States provided $505.6 billion in currency to China. They are of equal value, since currency is only a symbol of the value of goods. China imported $130 billion worth of goods from the United States and provided $130 billion in currency to the United States. The two are equal in value. Where is the unfair trade?

Trade Deficit Expansion Has Not Resulted in Job Loss

In H1 2018, the U.S. trade deficit rose to near historic levels, but the jobless rate fell to an almost 20 year low, down by 3.8 percent.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, total employment in the goods-producing sector reached 20.73 million in July 2018, an increase of 0.69 million or 3.4 percent from 2017. Employment in the manufacturing sector was 12.75 million, up 0.33 million or 2.7 percent from a year ago.

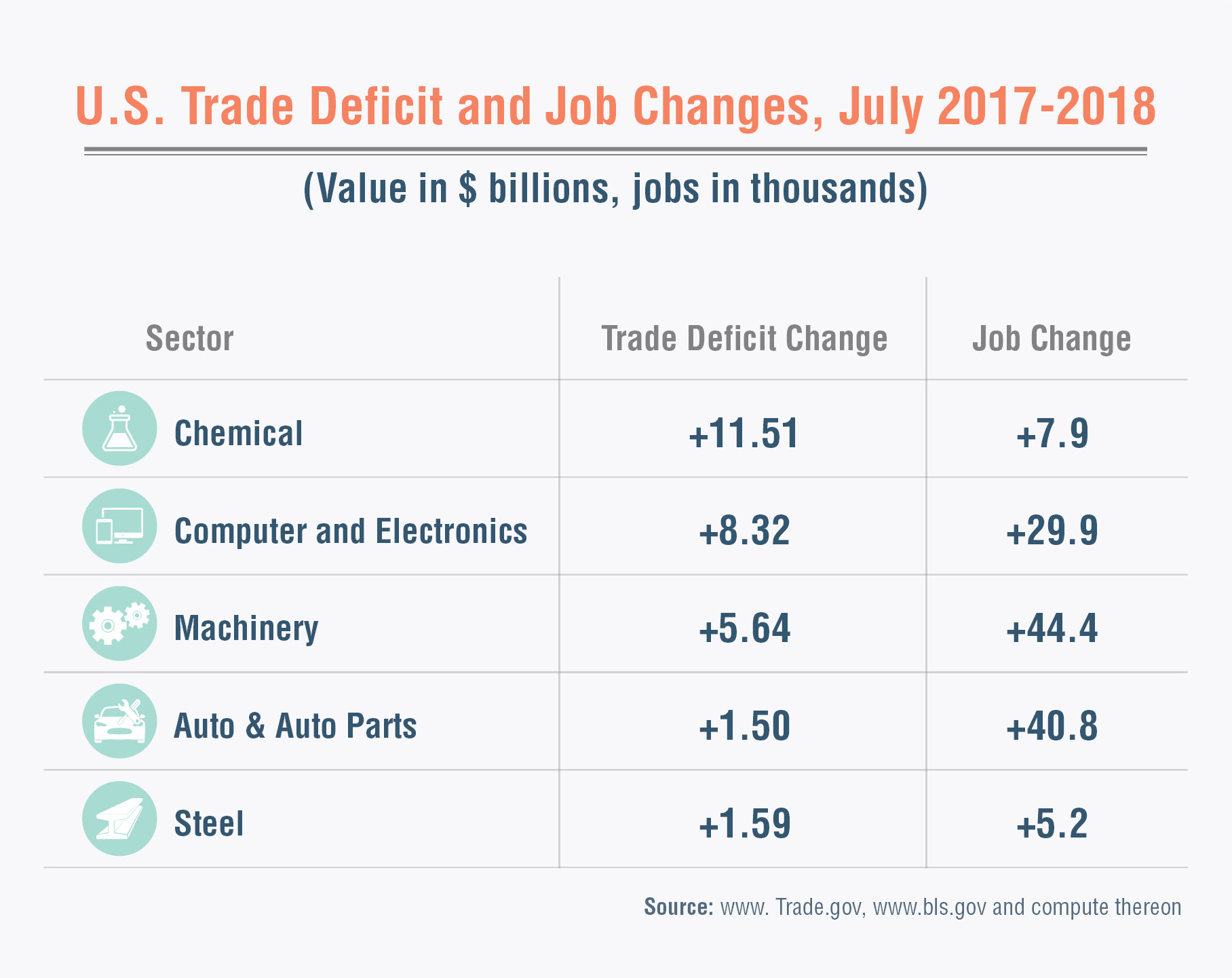

A sector comparison between the deficit and job changes proved the same findings.

A retrospective examination leads to the same conclusion. In all of 2017, the U.S. global trade deficit increased by $59.48 billion. By March 2018, total employment in the manufacturing sector had increased by 232,000 over the previous year. Among the six major deficit sectors, five of them saw a deficit increase, namely, computers and electronics (up $21.82 billion), transportation equipment (up $9.09 billion), oil and gas (up $12.13 billion), electrical equipment and appliances (up $6.64 billion), and machinery (up $8.42 billion). Only the clothing sector had a slight deficit decline of $335 million. Ironically, jobs increased in all five sectors by 22,000, 18,500, 5,200, 15,700 and 37,800, respectively. Only the clothing sector saw a job decrease of 6,200.

Interesting enough, trade surpluses can also lead to job losses. The aerospace sector is a flagship trade surplus earner for the United States. Its trade surplus increased from $70.34 billion in 2012 to $84.80 billion in 2017, a net increase of $14.46 billion or 20.1 percent. Total employment in the sector, on the other hand, fell from 498,600 to 484,600 during this same period, down 14,000 or 2.8 percent. Non-managerial employees fell from 290,500 to 263,000 or 9.5 percent! Apparently, the reason for the job losses is technological advances and not trade.

In conclusion, facts have proven repeatedly that the trade deficit is not a problem for the U.S. economy, trade or employment. There is no longer any need for the Trump administration to make trade balance its central goal since economic law cannot be changed simply by trade policies. The unilateral tariff measures imposed by the Trump administration—under the pretext of a trade deficit—block the normal global supply chain and trade flows and are completely wrong. Future developments will prove once again that they will do nothing but damage the world economy and ultimately, the U.S. economy as well.

The author is a Senior fellow of Center for China and Globalization(CCG), also a senior fellow of Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies, Renmin University of China

This article’s Chinese version was originally published on www.huanqiu.com.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +