Tu Youyou Took on the Virus and Saved Millions of Lives

Tu Youyou and her team have not only brought new hope to victims of malaria and other diseases, but also made a great contribution to the integration of Chinese and Western medicine.

What could be more horrible in this world than war? The answer is a virus — a time bomb ready to explode at any time, and in peacetime. In October 2015, a scientist named Tu Youyou came to the world’s attention when she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine for her major contribution to the treatment of malaria, a disease which people have suffered from for centuries. Of the 10 facts about malaria published by the World Health Organization(WHO) in 2016, the one that shocks people most is that about half of the world’s population is at risk of contracting malaria. In 2015, there were an estimated 212 million cases of malaria and an estimated 429,000 deaths from malaria.

Since the very first outbreak of malaria, people have been seeking a cure. The bark of the Cinchona tree, first discovered by indigenous people living in the tropics and subtropics, was found to be effective in treating malaria. Following centuries of continuous study, scientists extracted the most effective pharmacological component from it, and developed a drug named quinine.

Despite the availability of quinine, malaria continues to take a hefty toll on the health and lives of people around the world. In China alone, malaria raged for several centuries, even infecting Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty, who recovered only after taking quinine from missionaries.

The latest information in the World Malaria Report 2018 published by the World Health Organization (WHO) shows that an estimated 219 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide in 2017 (95% confidence interval[CI]: 203-262 million), compared with 239 million cases in 2010 (95% CI: 219-285 million) and 217 million cases in 2016 (95% CI: 200-259 million). In 2017, there were an estimated 435,000 deaths from malaria globally, compared with 451,000 estimated deaths in 2016, and 607,000 in 2010.

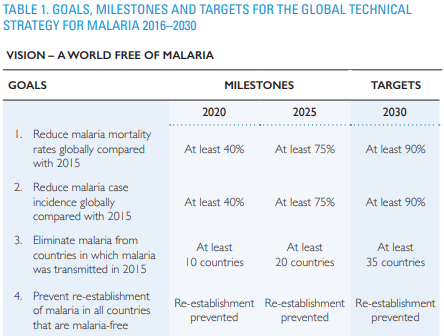

The WHO, which attaches great importance to the prevention and cure of malaria, introduced the GLOBAL TECHNICAL STRATEGY FOR MALARIA 2016-2030 in 2015. This strategy has been developed with the aim of helping countries reduce the human suffering caused by the world’s deadliest mosquito-borne disease, noted Dr. Margaret Chan, former Director-General of the WHO. By taking this strategy forward, countries will be able to make a major contribution to implementing the post-2015 sustainable development framework. A major scale-up of malaria response will not only help countries reach health-related targets for 2030, but also contribute to poverty reduction and other development goals.

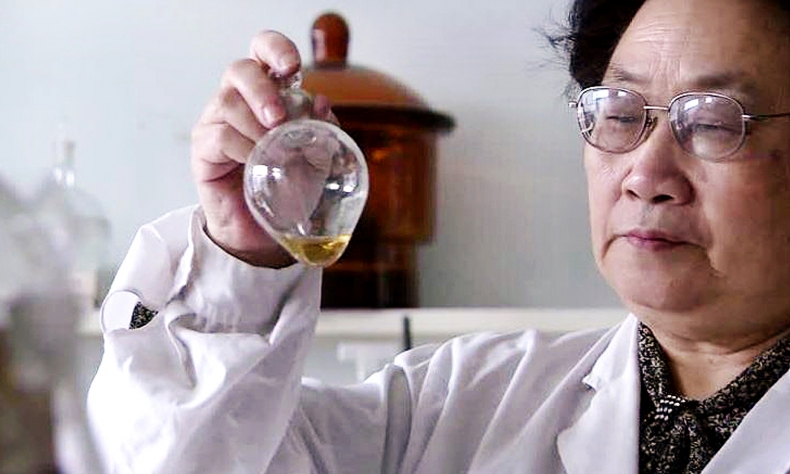

Tu Youyou, imperceptibly influenced by what she saw and heard regarding traditional Chinese medicine since an early age, has been committed to studying the integration of traditional Chinese medicine and Western medicine. In 1969, against the backdrop of rampant malaria, the China Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine began to develop antimalarial drugs. Later on, a book titled 640 Folk Prescriptions was compiled by Tu’s team, based on more than 2,000 prescriptions following a systematical collection of medical books, herbs and folk prescriptions from past dynasties. In addition, they had lab tests on over 200 kinds of traditional Chinese medicines, and experienced more than 380 failures, using modern medicine technology and methods for analysis and research to constantly improve the extraction of drugs. Finally, artemisia annua was successfully used to fight malaria in 1971, contributing to a sharp decrease in malaria cases in China from 2 million in 1980 to 900,000 in 1990.

Dr Li Lei, a geneticist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, said the discovery of artemisinin solves the problem of quinine resistance in malaria, allowing patients whose treatment was discontinued due to quinine’s ineffectiveness to be treated once again, saving tens of thousands of lives. As a readily available raw material, artemisia annua will become the more affordable, better drug for the victims of malaria in poor areas of Africa.

If plasmodium develops resistance to quinine, could that not also happen to artemisinin used for later treatment? In fact, the first evidence of malaria’s resistance to artemisinin has already been found in Southeast Asia, where artemisinin was first widely used. Studies by the WHO and countries in Southeast Asia have found that in countries of the Greater Mekong Subregion, such as Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar and Vietnam, signs have been observed including the slow elimination of plasmodium and drug resistance to artemisinin over a three-day period during which people infected with malaria were treated with artemisinin-based combination therapy.

Yuan Lanfeng, Doctor of chemistry, university of science and technology of China, said in 2018 that the emergence of plasmodium falciparum resistance to artemisinin was a corollary of evolutionary theory, since it is the result from pathogens undergoing natural selection under the circumstance of drugs. Microbes have a short life cycle and are evolving rapidly, so this is a long-run battle that humans are likely to lose.

On April 26, 2019, the 12th World Malaria Day, the latest research findings from Tu’s team were published by The New England Journal of Medicine. The team proposed new treatments for artemisinin resistance: an extension of the treatment period from three days to five or seven days, as well as the replacement of adjuvant drugs to which the drug resistance has developed in artemisinin-based combination therapy.

Tu Youyou believes that resolving artemisinin resistance is of great significance. On the one hand, Tu and her team remain committed to artemisinin research in alignment with global vision, because, for a long period into the future, artemisinin is set to remain the most effective anti-malaria drug. On the other hand, because of the low cost of artemisinin antimalarials, each course of treatment costs only a few dollars, making it affordable for the vast number of people in poor areas of Africa where the epidemic is concentrated. This brings humans closer to the goal of achieving the goal of global elimination of malaria.

Pedro Alonso, director of the WHO Global Malaria Program, noted that the artemisinin-based combination therapy has cured billions of victims of malaria. Alonso praised Tu’s team for its great contribution to anti-malaria research.

Although humans have taken one step ahead in the race against virus, there remains a long way to go. However, it bought more time for mankind in this fight against malaria, which is a great achievement. The great pharmacists, just like the person described by philosopher Albert Camus in his work called The Myth of Sisyphus, stands “beyond his own destiny. He is harder than the boulder he moved.”

In the midst of new developments in drug resistance in artemisinin, Tu’s team found that dihydroartemisinin had a positive effect on the treatment of highly variable lupus erythematosus. No unexpected adverse events occurred in the first group of volunteers currently involved in the clinical trial. Clinical trials typically include three phases, with more samples needed in Phase II and III, so the process will take at least seven to eight more years. If the trial goes well, it is expected that the new dihydroartemisinin tablets may be available on the market as soon as around 2026. There are currently signs indicating that artemisinin is effective in treating lupus erythematosus and this is cause for cautious optimism, Tu said.

Tu Youyou and her team have not only brought new hope to victims of malaria and other diseases, but also made a great contribution to the integration of Chinese and Western medicine. The Chinese Academy of Traditional Chinese Medicine has noted that the works on artemisinin and other traditional Chinese medicines, written by members of Tu’s team, are expected to be included for the first time in the forthcoming sixth edition of the Oxford Textbook of Medicine, a globally authoritative textbook of medicine. Industry insiders believe that this will be considered one of the most significant outcomes of Chinese medicine in its efforts to “go global”.

Professor Timothy M. Cox, Editor in Chief of the Oxford Textbook of Medicine, said he is glad that traditional Chinese medicine is set to be included. The chapter on traditional Chinese medicine is both important and profound, a credit to the efforts of Chinese scientists, he said.

On December 6, 2018, a white paper on Chinese medicine was published by the State Council. It points out that the program of traditional Chinese medicine has become a national strategy and has entered a new historical development period.

Tu’s team builds a bridge between traditional and modern medicine, allowing traditional Chinese medicine therapy not only to be widely used in China, but also approved by more and more countries for its effective treatment. The development of artemisinin and the contribution made by Tu’s team have led the world to realize that traditional Chinese medicine is an integral part of international medical development, and is no longer seen as a mysterious or black art of China. We hope that the combination of Chinese and Western medicine in global health governance will show the significance of traditional Chinese medicine!

By Dong Lingyi

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +