China’s New Role as Defender of Intellectual Property

China recorded the highest number of international patent applications in 2019, outstripping the US in the process, and is another milestone in the country’s IP story over the past forty years. How did it manage it?

On April 26 the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) will celebrate fifty years of protecting intellectual property throughout the world through 23 international treaties. Since 1970 it has presided over what has become one of the most important signs of a country’s economic strength and industrial know-how, registering and deliberating on 100,000s of patents from 193 different countries.

Of those countries, the rise of China as an important player in IP protection has been one of the organisation’s and the country’s greatest success stories to date. China has gone from a country where IP was “almost unknown” according to Tian Lipu, Commissioner of the National Intellectual Property Administration in China (CNIPA), to the world’s top patent filer in just forty-years of membership.

From little regulation to expansive framework

China’s first foray into IP protection came in 1980 and its membership with the WIPO. Having just embarked on greater interaction with the rest of the world following Deng Xiaoping’s 1978 Reform and Opening-Up policy, the government quickly established the building blocks for its own domestic IP protection with the creation of the Trade Mark Law (1982), Patent Law (1984) and the PRC Copy Right Law (1990).

Those initial years were characterised by China’s “produce-and-copy economy”, which turned a blind eye to copyright infringements in the pursuit of economic growth. There was also a lack of awareness regarding IP infringements, as highlighted by an absence of IPR training centres, which wouldn’t be established until 1996. The first twenty years therefore were a steep learning curve however as former WIPO Director-General Dr. Arpad Bogsch said, “China had accomplished all this at a speed unmatched in the history of intellectual property protection.”

In 2001 and fresh from its accession to the World Trade Organisation, the Chinese government ratified the Agreement on Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights, which saw the start of its own domestic IPP infrastructure reaching international standards. At the time, China’s economy was starting to transition from a manufacturing-based economy towards an innovative one and it was therefore essential for the country to have an IPP framework “as hard as steel and definitely not soft as bean curd”, as said by former Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao.

It launched the Compendium of China’s National Intellectual Property Strategy in 2008 to help initiate that steel, incorporating 280 detailed measures and plans for 16 national campaigns to fight IP piracy and infringement. Tian Lipu called it “a turning point” in China’s engagement with IP and indicated the country’s “steadfast determination to encourage innovation and create a knowledge-based economy”.

With that, amendments to China’s existing IPP laws came thick and fast. IP courts located in Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou were established in 2014, as well as the introduction of guideline cases to help judges implement consistent IP rulings. It also coincided with a boom in patent filings, with China rising to become the first country to file more than one million patents in a single year from its domestic patent office, and third in overall oversee patent fillings with 42,154 registered in 2015, having only recorded 2503 ten years before.

Trump presidency and more IP reform

China’s first thirty-five years brought plenty of reform to domestic IP and the influx of foreign companies but there were still questions about its overall effectiveness. 2016 therefore saw the government take new steps to ensure it could protect the breakthroughs in “next generation information and communications” as laid out at the 13th CPC’s Party Congress.

With those industries expected to be worth billions of dollars and essential for future innovation, with technology such as face recognition expected to be worth US$6.5 billion by 2021 alone, the government set forth to establish an even higher set of legal rules to protect its innovative start-ups like Yitu Technology and DeepGlint, as well as international companies that would partner them on this journey.

But 2016 also coincided with the US Presidential Election victory of Donald Trump, which brought a chaos to China-US relations, especially on IP protection. President Trump was especially vehement in criticising Beijing over IP theft, which amalgamated itself into a long-standing trade war which has not yet been resolved.

Despite this challenge, the country continued to reform as planned, passing some of its most important and wide sweeping amendments, countering President Trump’s accusations.

On January 4 last year a new version of the Draft Amendments to the Patent Law was published for public consultation, aiming to further strengthen the protection of legitimate patent owners. Among the key amendments proposed were aims to protect inventor rights from within companies, a voluntary licensing mechanism for patentees and rises to fines for patent infringement ranging from 100,000 yuan (US$14,210) to five million yuan (US$710,500), up from 10,000 yuan to one million (US$142,100) in the current law.

Amendments to the Trade Mark Law were also implemented, with significant changes made to prohibit bad-faith trademark filings—a key grievance in many IP disputes—as well as strengthening the punishment for trade mark infringers from 3 million yuan (US$426,300) to 5 million yuan (US$710,500).

And a new guideline on Strengthening Intellectual Property Rights Protection was released by the General Office of the CPC Central Committee and the General Office of the State Council, outlining further plans to effectively curb IP infringements. The new directive pledges to cut IP violations by 2022 and create an improved IP protection system that will spur innovation by 2025.

In practical terms and addressing suggestions made by foreign companies, the government reformed IP courts by expanding them to twenty-three and were presented with new powers to give them “exclusive jurisdiction” when dealing with IP infringement cases. An appellate IP Court, similar in stature and function to the US Court of Appeals, was also created in 2019 to ensure a fairer and more transparent system.

Reforms were made to ensure technical investigators, expert assessors, and specialized IP judges were all “experienced and professional”, with judges needing at least 6 years’ of IP trial work before joining. According to William Weightman, an Analyst at Kobre & Kim LLP who has extensively researched Chinese intellectual property law China’s IP judges are now “amongst the best educated judges in China’s court system”.

Guiding cases have also become more widely used to assess judgments, going from just 10 in 2017 to 51 as of last year, according to the China Guiding Cases Project at Stanford Law School. Mei Gechlik, founder and director of the project has called the recent increase an “encouraging” sign and evidence that IP protection is gaining more value.

Now the largest International patent application filer

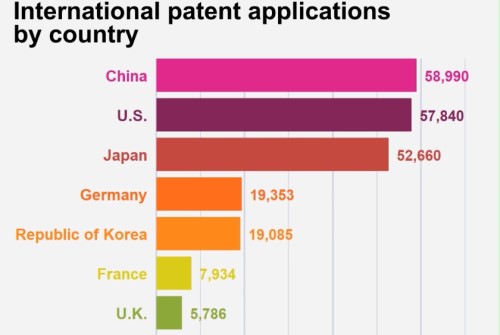

The announcement by the WIPO in April that the country had recorded the highest number of international patent applications in 2019, usurping the US in the process, is a further milestone in the country’s IP story over the past 40 years.

Last year, 58,990 patents were filed, a 200 percent-fold increase from the previous 20 years, when it only managed 276. Not only was it the country with the highest total patents filed, but Chinese telecommunications company Huawei was also found to be the company with the most filed for the third year running, while four of its universities also made-up the top ten of higher-education facilities filing patents, with Tsinghua University residing in second.

Its rise to the top of international patent applications and its year-on-year reforms to IP protection since it first gained membership to the WIPO is an almighty turnaround. Having once been labelled an IP novice and one of the world’s biggest infringers, China now stands as a guardian of IP protection and one of its most important defenders.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +