Did China Get Sri Lanka to Cough Up a Port?

“China got Sri Lanka to cough up a port,” said the New York Times in a widely quoted article published on June 25, 2018.The article claimed, “Every time Sri Lanka’s President Mahinda Rajapaksa turned to his Chinese allies for loans and assistance with an ambitious port project, the answer was yes.

“China got Sri Lanka to cough up a port,” said the New York Times in a widely quoted article published on June 25, 2018.

Δ The article claimed, “Every time Sri Lanka’s President Mahinda Rajapaksa turned to his Chinese allies for loans and assistance with an ambitious port project, the answer was yes.

“Yes, though feasibility studies said the port wouldn’t work. Yes, though other frequent lenders like India had refused. Yes, though Sri Lanka’s debt was ballooning rapidly under Mr. Rajapaksa,” the paper asserted.

Are the allegations true and fair?

Feasibility Studies on Hambantota Port

The Sri Lankan government has long wanted to build a seaport in Hambantota. Two feasibility studies were conducted before the Sri Lankan government embarked on the ambitious Hambantota port project.

Δ Container ships are pictured docked at the Colombo South Harbor, funded by China, in Colombo, Sri Lanka, July 26, 2016. (Image Credit: REUTERS/Dinuka Liyanawatt)

The first feasibility study was completed in 2003 by a Canadian engineering firm, SNC-Lavalin. However, it was rejected by the ministerial task force on the grounds that it was not bankable and was incomplete since the study overlooked the port’s potential impact on Colombo Port.

Three years later, Ramboll, a Danish consulting firm undertook a second feasibility study and adopted a more optimistic view of the potential of Hambantota Port. It projected that dry and bulk cargo would constitute the main traffic for the port until 2030. Hambantota Port was expected to handle approximately 20 million twenty-foot equivalent units by 2040.

Tsunami Devastates Hambantota

On December 26, 2004, a magnitude 9.1 earthquake with its epicenter off the west coast of Indonesia’s Sumatra island triggered a series of deadly tsunamis across the Indian Ocean, killing an estimated 230,000 people in 14 countries.

Δ The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake occurred at 00:58:53 UTC on 26 December with the epicentre off the west coast of Sumatra, Indonesia. The shock had a moment magnitude of 9.1–9.3 and a maximum Mercalli intensity of IX (Violent). Indonesia was the hardest-hit country, followed by Sri Lanka, India, and Thailand.

Sri Lanka was the second hardest hit. The strong waves wiped out entire villages and townships in the south and east coast of the island nation, caused 30,000 reported deaths, damaged highways and railways, destroyed schools and hospitals and left 900,000 people homeless.

Hambantota, a bustling southeastern coastal town known for its salt production, was completely devastated.

Hambantota Port Project not Initiated by China

Hambantota is home to Mahinda Rajapaksa, the sixth president of Sri Lanka, and his electoral district. When coming to power in November 2005, he wasted no time in launching several big-ticket infrastructure projects to revitalize the economy of his hometown. Hambantota Port, a project first mooted by his father, was one of them.

In a brief published in April 2018, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, an influential U.S. think tank, affirmed that Hambantota Port was not a China-initiated project. In fact, Hambantota Port was constructed long before the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was launched in 2013.

China’s Loan to Finance Development of Hambantota Port

India was the first country Rajapaksa turned to for financial help to build Hambantota Port. However, his request was rejected as India deemed the project economically unviable. The multilateral development banks, or MDBs, were also unwilling to lend their support to the project.

China saw the potential of Hambantota Port, which strategically lies a mere 10 nautical miles north of the busy Indian Ocean international shipping route. It not only meets the logistical needs of China’s burgeoning global trade, but also serves as a transshipment hub and a supply base providing bunkering facilities to the large number of vessels plying one of the busiest shipping routes in the world. India’s relaxation of its cabotage rules in May greatly enhanced Hambantota’s status as the transshipment port for goods destined for the subcontinent.

Δ Hambantota Port holds the expectation of Sri Lanka’s development.

Exim Bank of China eventually agreed to fund 85 percent of Hambantota Port’s Phase 1 construction costs after much negotiations. The 15-year commercial loan of $306 million carried an interest rate of 6.3 percent with a four-year moratorium.

“The Sri Lankan team did try to seek a preferential loan from China, but the quota of China’s preferential loans then to Sri Lanka had been used for the Norochcholai Coal Power Plant and other projects,” China explained in a Xinhua News Agency report in 2015.

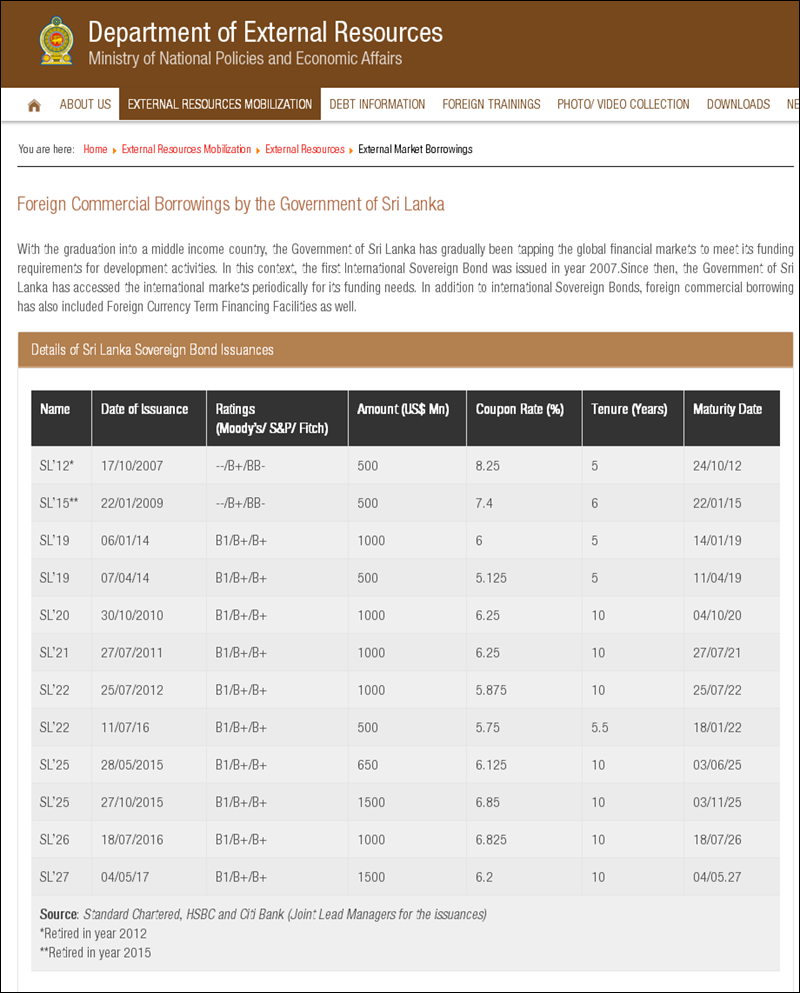

Sri Lanka was given two options for the interest rate: A 6.3 percent fixed rate or a floating rate pegged to the London Interbank Offered Rate, which was over 5 percent then and trending higher. In October 2007, Sri Lanka issued a Fitch BB-rated, 5-year sovereign bond at 8.25 percent, not surprising for the island nation that was still mired in a prolonged civil conflict with the Tamil Tigers.

Exim Bank of China later provided additional loans totaling $900 million to finance Phase 2 of the Hambantota Port project at 2 percent, a preferential rate enjoyed by 77 percent of Chinese loans to Sri Lanka.

Hambantota Port Suffered Losses After Opening

Construction work for Phase 1 of Hambantota Port, undertaken jointly by China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) and Sinohydro Corporation, commenced in January 2008. The port became operational on November 18, 2010, five months ahead of schedule.

However, Hambantota Port was unable to generate sufficient revenue to meet its loan obligations due to inadequate governance, lack of commercial and industrial activities, as well as its inability to attract passerby vessels to dock at the port. By the end of 2016, it suffered a total loss of $304 million.

Majority Control of Hambantota Port Goes to CMPH

Amid mounting pressure to meet the International Monetary Fund’s bailout terms and loan repayment obligations, the Sri Lankan government struck a public-private partnership (PPP) deal with China in July 2017, giving majority control of Hambantota Port to CMPH, which is listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE).

According to the filing made by CMPH to the HKSE, the terms of the concession agreement related to Hambantota Port were as follows:

- CMPH would make an investment of $1.12 billion in Sri Lanka, out of which $974 million would be used for the acquisition of 85 percent shares in the Hambantota International Port Group (HIPG), a company which was granted a 99-year term by the Sri Lankan government to develop, manage and operate Hambantota Port valued at $1.4 billion.

- HIPG would acquire 58 percent of Hambantota International Port Services (HIPS), which had been given the exclusive rights to develop, manage and operate the Common User Facility of Hambantota Port.

- The Sri Lanka Port Authority (SLPA) would hold 15 percent and 42 percent equity interest in HIPG and HIPS, respectively.

- The remaining $146 million would be deposited in CMPH’s Sri Lanka bank account for the purpose of future development of the port and marine-related activities.

- Within 10 years from the effective date of the concession agreement, SLPA has the right to buy back 20 percent shares of HIPG on terms mutually agreed upon.

- After 70 years, SLPA could acquire CMPH’s entire shareholdings in HIPG at a fair value to be determined by the valuers appointed by both parties.

- On expiry of 80 years, SLPA could buy up CMPH’s shareholdings in HIPG for $1, leaving CMPH with 40 percent shareholdings in HIPH.

- After 99 years, CMPH would transfer all its shareholdings in HIPG and HIPS to the Sri Lanka government and SLPA at a token price of $1 upon termination of the agreement.

The concession agreement went into effect on December 9, 2017.

To increase industrial and commercial activities at the port, China further undertook to develop a 50 sq. km economic zone and build a liquefied natural gas plant and a tourist dockyard. China will also invest between $400 million to $600 million to develop phase 3 of Hambantota Port which is expected to be completed by 2021.

The PPP thus is not a debt-equity swap but a fresh investment by CMPH amounting to $1.12 billion. The loan taken by SLPA for the construction of Hambantota Port was transferred to Sri Lanka’s treasury. CMPH’s investment in HIPG will be disbursed in three tranches of $292 million, $97 million and $584 million, with the balance of $146 million to be deposited in CMPH’s Sri Lanka bank account for future use.

Δ Photo taken on July 5, 2018 shows the scene of a media briefing held at the Chinese Embassy in Colombo, Sri Lanka. China is full of confidence in the future development of Sri Lanka and dismisses allegations that the island country faces a “debt trap,” the Chinese Embassy in Colombo said here Thursday. (Xinhua)

Hambantota Port: A Lesson China Learned

Sri Lanka had a dream; its government had a vision: To turn strategically-located Hambantota into one of the busiest ports in the world.

When its neighbor turned its back, when the MDBs were cold to the project, China provided the funding and built Hambantota Port with good intentions.

However, as the dream went sour, China got the blame. The storyline was twisted. Hambantota became the oft-cited case of “debt trap” under the BRI. China was accused of twisting Sri Lanka’s arm “to cough up a port.”

Hambantota is a lesson China should learn: BRI projects must be transparent. World perception is as important as the intention.

According to a recent report by the Financial Times, “China’s development banks—the biggest lenders in the sector worldwide—are ramping up co-operation with overseas financial institutions after problems with international investment projects.”

China’s Development Bank is now “considering combining its lending efforts with western financial institutions that require adherence to ‘international standards’—including open, competitive tenders for project contracts as well as public studies on environmental and social impacts,” the paper highlighted.

Perhaps China has learnt a lesson from Hambantota Port.

Koh King Kee is the Director of China Belt and Road Desk, Baker Tilly MH Advisory Sdn Bhd, Malaysia. The views expressed in this article are strictly personal.

Editor: Cai Hairuo

Intern Editor: Shou Pan

Opinion articles reflect the views of their authors, not necessarily those of China Focus

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +