Outbreaks Expose the Best and Worst of Society

Though the current coronavirus outbreak has only been with us a matter of months, society’s response to it has followed a similar pattern to previous health emergencies, with rises in extreme discrimination twined with examples of real compassion.

Public health emergencies have occurred between times throughout the world for centuries—from the Black Death in the thirteen hundreds, to the SARS outbreak in 2003—often exposing the best and worst parts of how we as a civilization handle a crisis.

Some, such as during the AIDS pandemic in the 1980s and 1990s, have shown us at our worst, ostracizing entire groups of society and discriminating against them based on our own misconceptions and prejudices.

Others however, like the 2004 Ebola outbreak, epitomize how when we, as the international community, come together as a one—charities, businessmen, musicians and the general public—we can help institutions and countries greatly in their fight.

Though the current coronavirus outbreak has only been with us a matter of months, society’s response to it has followed a similar pattern to previous health emergencies, with rises in extreme discrimination twined with examples of real compassion.

Sickening rise in xenophobia sentiment

Stories of excessive discriminatory attacks have been well reported, with instances of violence and racism occurring such as in the United Kingdom were Asian’s have been called a “virus” and told to return to their “country” whilst having stones thrown at them.

Similar accounts have been recorded by Chinese and Asian communities in France, Germany, Australia and the United States, where the latter in one instance saw a subway rider in Los Angeles spout a barrage of abuse at Chinese people, claiming that “every disease comes from China”.

Fear has in part driven this kind of sentiment, especially in places like South Korea, where cases of the virus have increased dramatically over the past few days. In Seoul, restaurants and shops have been reported donning signs that read “no Chinese allowed”, while political parties have started using nationalist sentiment to target Chinese people through travel bans.

Fear is of course no excuse for this behaviour, but when politicians make inflammatory remarks and call the coronavirus the “Wuhan virus” or the “Chinese virus”, there can be little surprise when such bigoted action occurs. This has also been perpetuated by some of the world’s media, who have at times run incredibly callous headlines such as the “Sick Man of Asia” or “Yellow Peril”. Their actions are strikingly reminiscent of the way homosexuals were victimized during the AIDS pandemic, when it was portrayed by the media as the “Gay Plague”.

As the virus disperses itself further across the world, that sentiment is now being felt in other communities. In Ukraine on February 20, 45 Ukrainian nationals and 27 foreign nationals arrived in the small town of Novi Sanzhary for quarantining after being evacuated from the Chinese city of Wuhan, the centre of the epidemic. Rather than being met with compassion or understanding, the 72 people encountered a scene from a medieval drama, with stones being thrown and bonfires lit in an effort to keep them out. Despite the majority of those entering being fellow countrymen and women who had not contracted the virus, the fact that they had come from Wuhan was enough to organize such a mass protest.

Solidarity is important and precious to humans

Fear or no fear, the actions of some against Chinese and Asian communities has been excessive, and it is right to wonder if this level of scrutiny would have been attached to people from a different country or race.

But out of such darkness has also come light, with many in the world shunning prejudice in favour of helping those fighting the coronavirus in their hour of need.

Politicians across the world have shown their support for China as it battles the virus, from South Korea President Moon Jue-in to French President Emmanuel Macron. Celebrities have come out to donate money in their millions, from Bill and Melinda Gates, to others such as Justin Bieber and Cristiano Ronaldo. Charities including The Red Cross have acted greatly to help aid China’s fight, with more than US$4 million donated as of February 19 by its Singapore branch.

Ordinary people have also put their money where their mouth is, setting up some 1,393 Go Fund Me pages (as of February 25) from countries ranging from Germany to the United States, Australia to the United Kingdom, all in the name of helping fight the virus. One of those, the Wuhan University Alumni Association of Greater New York, has raised over US$700,000, donating five Non-invasive Ventilators and ECG monitors to two hospitals on the front line: Leishenshan Hospital and Tongji Taikang hospital in Wuhan.

In Australia, to combat declining numbers at Chinese restaurants—with some having reported drops of as much as 50 percent and others closing—a campaign has begun to get bums back on seats. #IWillEatWithYou has been trending in Australia, with hundreds of people posting pictures of themselves eating at their favourite Chinese restaurants in a sign of solidarity, including Australian politician Senator Penny Wong.

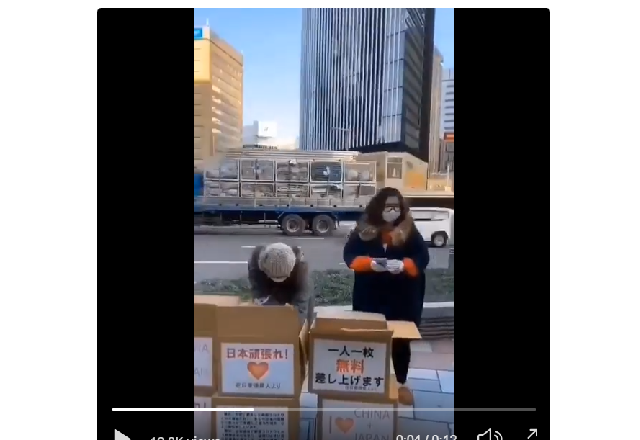

And as the virus continues to spread across the globe, Chinese communities abroad are also doing what they can to help. In Japan, Chinese nationals have been seen handing out facemasks in the street due to shortages, as have Chinese locals in city of Manila, Philippines. The Chinese Embassy in Japan has also announced it will aid in sending inspection kits to the country, again because of shortages.

There is a chance the coronavirus will not be a short-lived health emergency given the recent rise in cases outside of China. But it is hoped that the world can show compassion, help and understanding to those affected by it in countries like Italy, Iran, South Korea and Japan, and elsewhere, something that regrettably not all Chinese people can say they have experienced.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +