The Ramifications of Johnson’s 5G U-Turn for Britain, Huawei & Sino-UK Ties

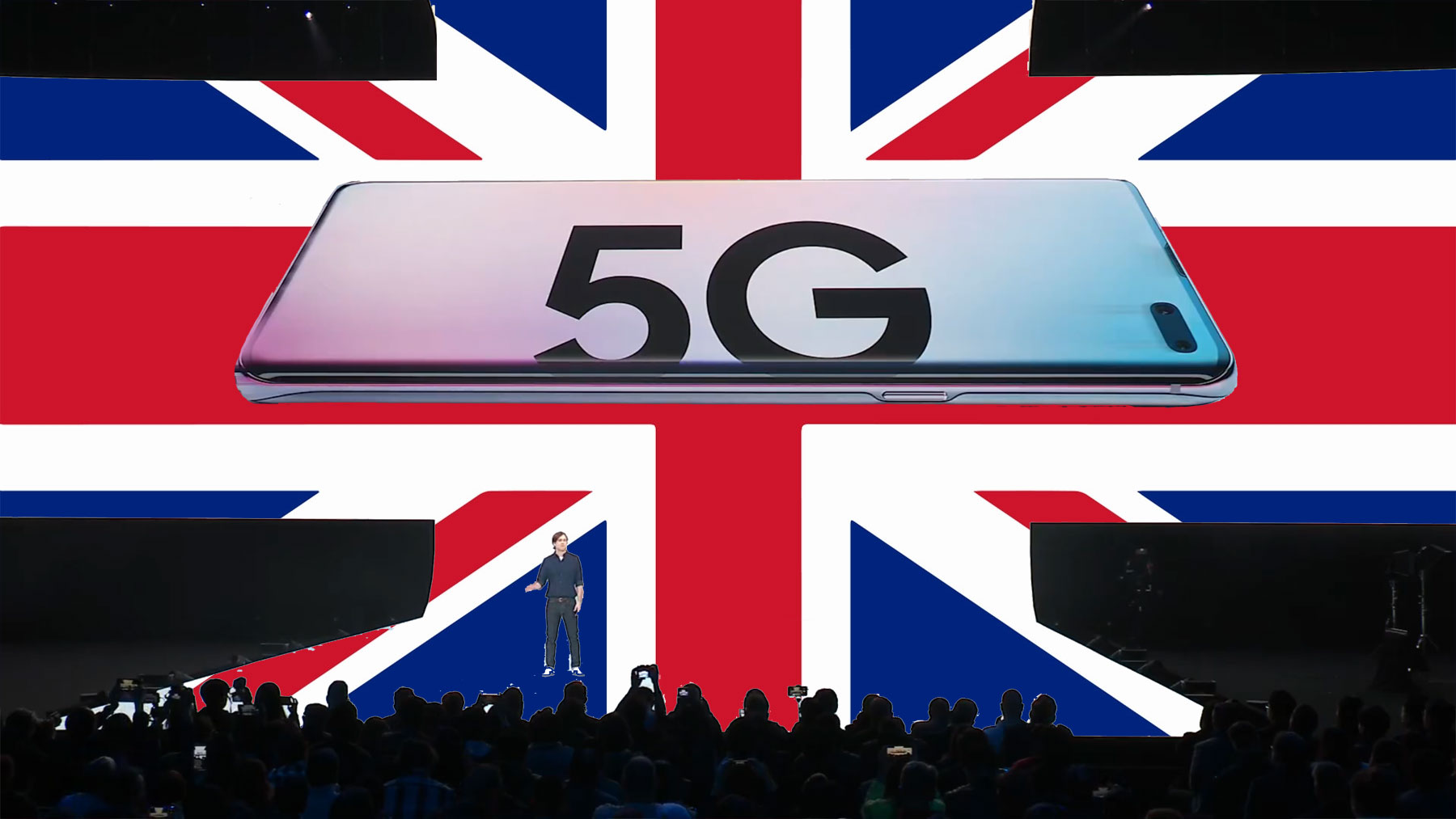

The UK looks set to reverse its decision to allow Chinese telecom giant Huawei to build part of its 5G network, a decision that threatens the UK’s position post-Brexit, Huawei’s long-term future and the China-UK relationship.

On January 28 UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson announced that Chinese tech firm Huawei would help construct the UK’s 5G network as he looked to turn his dream of a “connected Kingdom” into reality.

The final decision to allow Huawei access to the networks “non-core” parts—a decision that riled US officials—allowed Johnson to finally close the book on an issue that had troubled former prime ministers and China-UK relations in recent years.

Six months on from the decision however and the Chinese company’s role in the UK’s network is once again under threat, potentially causing serious problems for the UK economy, Huawei’s long-term future and crucially Britain’s continued relationship with China.

What has caused the sudden U-turn?

The expected change of course, which has not yet been officially confirmed, comes in response to new sanctions from the US government on Huawei introduced in May.

The new rules severely limit the company’s ability to design and manufacture semiconductors—integral to wireless internet units—by banning any company using US technology in its chips from selling to Huawei. This includes the software needed to print the chipset, of which the majority is owned or has ties to US companies.

Consequently, once the ban begins in September, Huawei will effectively be unable to use the equipment needed to print chips and thus in theory unable to provide the expertise and equipment needed to help build Britain’s 5G network.

What is more, The US Federal Telecommunication Commission (FCC) announced on June 30 a ban of buying Huawei and ZTE equipment by US companies with federal fiscal support.

In response to the US new measures, the UK’s National Cyber Security Centre, an arm of British governments intelligence and security organisation GCHQ, has been investigating the potential effects of them. While the report is expected to be published next week, senior officials have already suggested that it will propose revising the UK’s original decision and advise the government to ban Huawei from the network.

“Given that those sanctions are targeted at 5G and [are] extensive, it is likely to have an impact on the viability of Huawei as a provider for the 5G network,” cabinet minister Oliver Dowden told a special defence select committee on Tuesday.

Costly for UK telecom operators and economy

The news is a severe blow for the UK’s wireless network, which was set to be utilized as a vital tool in its post-Brexit economy.

For the country’s four major telecom operators, who all already use Huawei equipment or software in their networks, the U-turn is expected to cost £1.5 billion according to Enders Analysis, with the operators needing to not only remove any 5G equipment, but all of Huawei’s 4G equipment already installed.

But by far the biggest costs could be to the British economy. Stripping out Huawei’s equipment and replacing it with one of its competitors could take up to two years resulting in the loss of up to £6.8 billion to Britain’s coffers, according to Assembly Research. Their report, commissioned by Mobile UK in 2019, based the figure on the government’s own estimates regarding the benefits of a 5G network, and expect the impact of any delay to cause a loss of inward investment and lost productivity gains through stagnation of its digital infrastructure.

The UK’s leadership in 5G would also be lost if it were forced to spend money and time replacing equipment, according to Scott Petty, the CTO of British telecom operator Vodafone, as well as the benefits of leading in an industry where many western countries have yet to begin operating in.

Huawei risks its “survival”

The move also has serious ramifications for Huawei, not just in its UK operations, but for its long-term plans across Europe and North America.

Despite its reputation as a leader in 5G technology, winning 91 contracts for 5G installation globally, the company has a limited client base in Europe, with most of its contracts secured in Asia and Africa. Building the UK’s 5G network was therefore considered a lucrative coup for the company, and one that could have potentially opened doors to other western markets including in the EU, Canada and New Zealand.

A reverse in policy however makes securing these contracts more difficult. Countries will be alert to the potential pitfalls of Huawei’s equipment if it is no longer able to reliably manufacture it, and with the US increasingly putting pressure on allies to ban the company from any part of their networks, the company’s tough sell will only become harder in the future.

In the long-term, the company’s entire future could potentially be in jeopardy. Upon learning of the US’ decision, Huawei’s rotating chairman Guo Ping claimed the company were struggling for “survival”, and while it continues to be a success domestically with net profits of $9 billion in 2019, up 5.65 percent from the year before, there are fears that’s its dominance in the 5G field will be difficult to sustain as competitors close the gap further.

Question marks over Johnson and China-UK relations

Prime Minister Johnson’s move to resist President Trump’s calls to ban the telecom company in January were widely praised at the time for proving that Britain was prepared to look beyond its immediate friends to secure its best post-Brexit deal.

While the new sanctions offer legitimate reason for concern as to how Huawei can ensure the stability of its equipment, the timing of the decision is somewhat fortuitous for the British prime minister. Despite his overwhelming majority in parliament, Johnson was expected to face defeat over the use of Huawei equipment, with some backbenchers becoming increasingly vocal in their disapproval of the project.

It also comes as Sino-UK relations are facing their most challenging period since former prime minister David Cameron infuriated Beijing by meeting with the Dalai Lama in 2012. Issues over the coronavirus, Hong Kong’s national security legislation and the UK government’s recent decision to offer up to five years residence to up to 3 million Hong Kong citizens with BNO passports, has provoked a strong response in Beijing against the UK.

Huawei is a similarly sensitive subject, and Chinese ambassador to the UK Liu Xiaoming has made clear that China would see any decision to ban the company on unjust grounds as a legitimate reason for Chinese businesses to turn away from UK investment, especially in key infrastructure projects which Britain needs to secure its future.

Whether the US sanction can be deemed unjust grounds for a U-turn remains to be seen, but there is no doubt it is putting Sino-UK relations back under the spotlight. The UK for its part has stated that it wants a progressive relationship with China—Johnson on June 30 rejected the idea that he is a “Sinophobe” and his foreign secretary Dominic Rabb reiterated on Wednesday that Britain wants a “positive relationship with China” that recognises “its growth, its stature and the powerful role it can play”.

That being said, a reverse of January’s decision could be construed that Britain is not “a true friend or partner of China”, as ambassador Liu said in June, and as such is no longer deserving of the privileges and investment that such a relationship entails.

The release of the GCHQ report next week is therefore critical not only for the UK’s 5G network and Huawei’s future, but potentially the wider context of Sino-UK relations.

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +