UK’s Risky Move on Huawei and Hong Kong Won’t Benefit Itself

The UK’s position on Hong Kong is not about rights, freedoms or any other noble ideal. It is about politics plain and simple. Equally, the cutting of ties with Huawei is not about any perceived threat of surveillance or too much dependence on China, again it is about politics.

When the EU referendum was being bitterly fought in the UK in 2016, Brexit campaigners promised voters a world laden with freedom and opportunity.

If Britain is only able to unshackle itself from the dictates of Brussels, they said, the UK will then be free to develop much stronger economic relations with countries across the globe. China included.

The ardent Brexiteer and UK Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, confirmed as much in his “Global Britain” speech in February. “We are re-emerging after decades of hibernation as a campaigner for global free trade… The opportunities are extraordinary,” Johnson confidently announced.

Ideologues lapped up the prime ministers lyrical waxing of a Britain ready to emerge as a “supercharged champion” and defender of “the right of populations to buy and sell freely amongst each other.”

Critics however, were far from impressed.

No amount of pontificating and bluster could mask the reality that a Britain outside of the EU, is a Britain with much less clout on the world-stage. There was also a creeping fear that a post-Brexit Britain could find itself increasingly at the mercy of US policy makers, risking being pulled further into Washington’s orbit.

Given what has been witnessed over the last couple of weeks — specifically regarding the UK’s shift in foreign policy towards China — the fear of becoming a satellite of Washington, appears to have been well-founded.

U-turn on Huawei

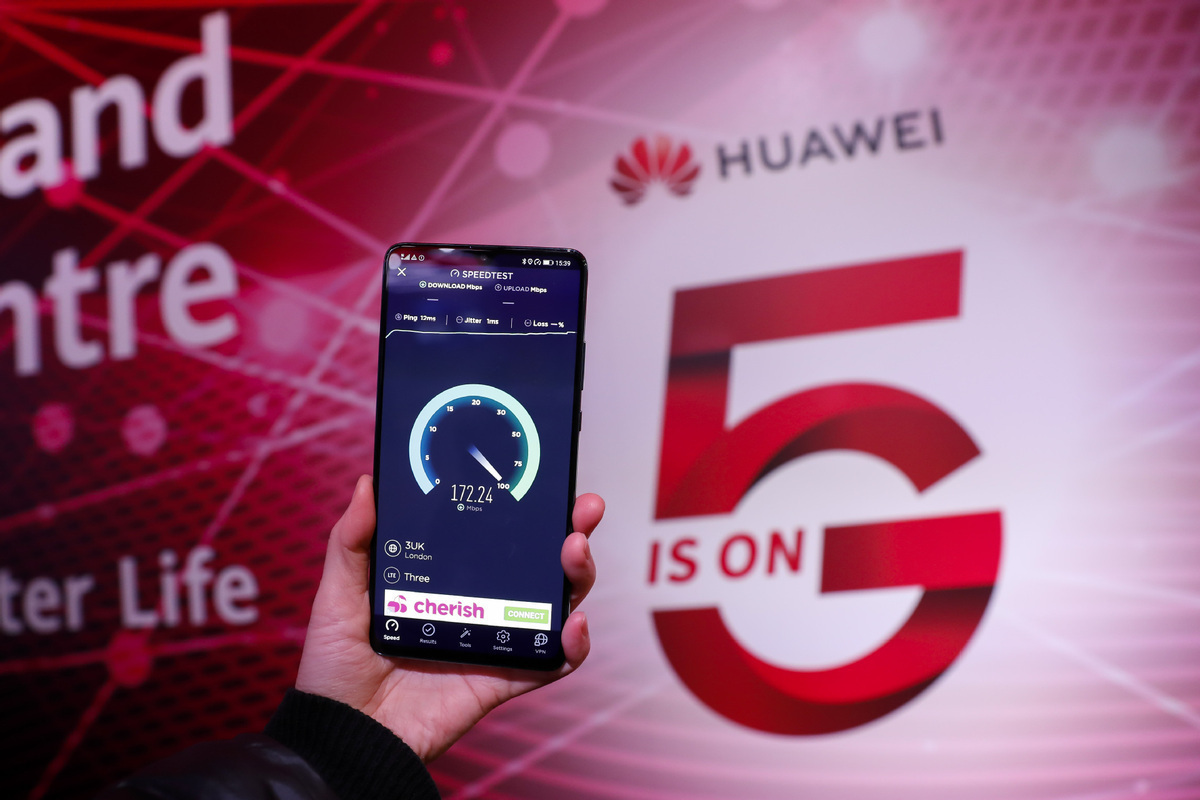

Boris Johnson bowed to growing pressure over Huawei’s involvement in the UK’s 5G infrastructure and is now intent on leading an international campaign to isolate the Chinese telecom giant.

Until a couple of weeks ago, Johnson was content in allowing Huawei to build and maintain up to 35 percent of Britain’s next generation telecommunications network. He has since announced plans to reduce all involvement of the China-based company in Britain’s 5G network by 2023.

The move no-doubt delighted anti-China hawks in the Whitehouse who have long been pressuring the UK and others to rethink their relations with Huawei or face severe repercussions. But it has presented a considerable problem for the UK.

At present, there is no company able to provide 5G technology at a similar cost to Huawei. And with the 5G revolution steaming ahead — with or without the UK — Britain faces the very real prospect of being left behind.

In an attempt to stop such a scenario from materializing, the UK government believes it has a plan. Johnson wants to establish a 10-nation alliance in an effort to create a company to rival the Chinese telecom giant. The proposed coalition, dubbed the “D10 club” would ideally consist of the G7 nations plus Australia, India and South Korea.

Naturally, the announcement to blacklist Huawei has received criticism in Beijing. Reflecting a possible government mindset, the Global Times stated that if the UK joins the US in waging a “technological Cold War” against China, it could not expect to maintain current economic and trading relations.

It is not yet clear whether other would-be D10 nations have the appetite to take such an adversarial position towards China. Though the topic is expected to feature prominently during this year’s annual G7 meeting hosted by Donald Trump set to begin on June 10, but has been postponed to September.

Tough voice on Hong Kong

In a move that has drawn further condemnation from Beijing, Johnson has waded into the Hong Kong debacle, offering a 12-month extendable visa to about 300,000 Hong Kong SAR citizens with BNO passports.

“If China imposes its national security law, the British government will change its immigration rules and allow any holder of these passports from Hong Kong to come to the UK for a renewable period of 12 months and be given further immigration rights including the right to work which would place them on the route to citizenship”, Johnson said.

Beijing has since urged London to stop interfering and warned that its residency offer would “backfire”, as all BNO passport holders in Hong Kong are Chinese citizens.

“We advise the UK to step back from the brink, abandon their Cold War mentality and colonial mindset, and recognize and respect the fact that Hong Kong has returned” to China, said foreign ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian.

Johnson claims the proposed Hong Kong national security legislation will undermine the “One Country Two Systems” principle which the Sino-British Joint Declaration mandates the UK has a duty to uphold.

The problem with this argument is that it is refuted by Hong Kong’s political leaders, British-owned Hong Kong-based businesses, and much of the wider international community who believe that China, not only has the right to protect its national security, but that the bill will actually provide a more stable business environment, and thus strengthen the “One Country Two Systems”.

“The 51st state”

Viewing the UK’s announcement on Hong Kong SAR citizenship and Huawei telecom contracts as independent from each other is an easy mistake to make. On the surface, the two appear unrelated.

The two issues however are inextricable intertwined. They represent a significant shift in the Britain’s foreign policy towards China, and its foreign policy towards the United States.

Until recently, London had at least tried to save face over its embarrassingly subservient “special relationship” with Washington. Now, Johnson is no longer even attempting to maintain the illusion about the influence the US wields over the UK.

The fact that his government has been so vocal about protecting the rights and freedoms of Hong Kong protesters, yet refuses to condemn President Trump over his actions towards protesters and the threat to call in the Army, speaks volumes.

The UK’s position on Hong Kong is not about rights, freedoms or any other noble ideal. It is about politics plain and simple. Equally, the cutting of ties with Huawei is not about any perceived threat of surveillance or too much dependence on China, again it is about politics.

China and the US are sliding to the fringe of a Cold War, and the UK, appears to have chosen its side.

Ignoring for a moment the very real danger of a Cold War turning hot, consider the economic consequences of Britain’s chosen trajectory. Consider a post-Brexit Britain cutting itself off from one of the fastest rising economies and the single largest market on the planet, at the very moment it needs to develop its relations. Consider doing all this in order to maintain a vastly unequal relationship with a hyper-nationalistic and increasingly hostile country.

Why burn a bridge to jump on a sinking ship?

Facebook

Facebook

Twitter

Twitter

Linkedin

Linkedin

Google +

Google +